[This transcript was generated by AI, so while I’ve checked over it, it may contain small errors.]

REBECCA: Hi, I'm Rebecca Lowe, and welcome to Working Definition, the new philosophy podcast in which I talk with different philosophical guests about different philosophical concepts with the aim of reaching a rough, accessible, but rigorous working definition.

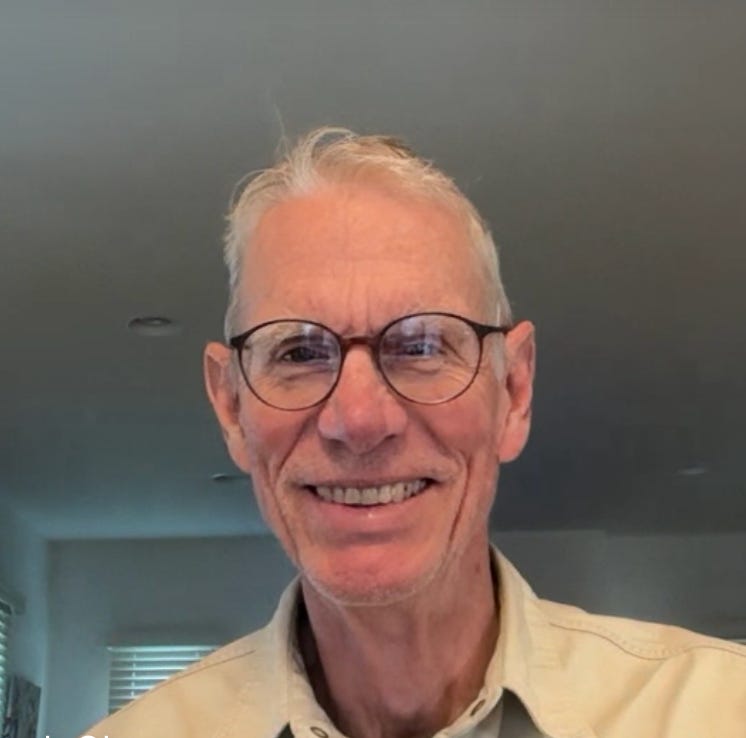

Today, I'm joined by Josh Ober. Josh is a professor of political science and classics at Stanford University, and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, where he's the founder and faculty director of the Stanford Civics Initiative. Josh's scholarship focuses on historical institutionalism and political theory, especially democratic theory, and the contemporary relevance of the political thought and practice of the ancient Greek world. He is the author of a number of excellent books, most recently The Civic Bargain, The Greeks and the Rational, and Demopolis: Democracy Before Liberalism.

He's also one of my favorite people to talk with. And today we're going to be talking about democracy: what it is, but also why it is what it is, what it needs, what it gives us, why it matters, how it differs from other things like it, what it asks of you, and where you might find it. Thanks for joining me, Josh.

JOSH: Thank you so much, Rebecca. Delighted to have this conversation with you.

REBECCA: So I thought I'd begin by offering you some options. This seemed appropriate for a conversation about democracy. So here are your options, Josh. You get three of them. And they’re options on how we begin this discussion.

The first option is we start by agreeing on some minimal, functional, non-controversial definition of democracy that we can bank for later and also use as a starting point for now. The second option is we start with your fuller account of democracy: two or three minutes to hold forth on its details, and value, and implications, relation to other concepts. And the third option is we start more descriptively with you talking about a place, current, historical, or imaginary that you think clearly counts as a democracy.

Okay, so you can pick between: one, minimal definition; two, full Josh account; three, descriptive story. Where do you want to cast your vote?

JOSH: Good. Why don't we vote for number one? Because I do have a minimal definition for democracy that I believe is the shortest one that anyone has ever offered. It has indeed fewer syllables than the word democracy. So the basic definition of democracy is no boss.

Now, there is a slight addendum that I have to put to that. No boss other than ourselves. And then we're going to have to think about who we are and so on. But I think that's the basic definition of democracy — it’s the rejection of the idea that there is an external boss who would be legitimately, or in our own interests, ruling over us.

REBECCA: I love it. It certainly appeals to my kind of natural sense of hating constraint, hating other people to tell me what to do. Are there any risks with this as a minimal definition? So I like that you added some caveats, because no boss… I mean, there are other situations in which we might think you've got no boss and you probably don't want to count them as democracies. Do you think there are any other potential weaknesses in this minimal definition?

JOSH: Oh sure. I mean I think then, once we say that, we have to say well under what conditions is it actually going to work for us to rule ourselves. And if ruling ourselves… rejecting a boss, means that we give up on basic security or basic welfare. If we're hungry, if we're constantly in fear, then obviously it's not going to work.

I think there are very good reasons that people like to live without a boss. It's not the only option for living well, or for people to believe that they're living a good life. But I think there are very good reasons for it. But, you know, frankly, if you have to give up on the basic notions of security and welfare, my guess is you're going to say, unfortunately, life, decent life, requires a boss. So that's, I think, absolutely key.

And that sort of gets us to an issue that is really important, I think, for any kind of democratic theory, or democratic practice, is that if democracy can't deliver the basic goods of human existence, then it's going to be written off as a nice idea that didn't work. So, you know, if you go back to Thomas Hobbes: Hobbes says, why do people create a social contract? Why are people going to need or why will they willingly create a boss? Hobbes is the master of boss politics. He says: in order to get security and welfare. That that's the only way to get it.

So democracy ultimately, I think, says Hobbes might be wrong. And if he is wrong, then we could have this condition of not having a boss other than ourselves. But I think that's the fundamental requirement that democracy is going to have to meet.

Now, there are going to be other issues that will come up as we talk, I'm sure, about questions of rights, questions of the basic goods that are other than security and welfare. But I think it's important to start there. To simply say that if it's a nice idea that doesn't work in terms of giving human beings a chance at a fundamentally decent existence, then it's not going to be… it’s not going to be valuable.

REBECCA: Okay, so let's take that as our kind of starter. And we'll come back to these important questions about the conditions under which it successfully obtains, what it can bring us, the criticisms people have made about whether it does bring us those things.

First, I just want to dial back a second and ask you this question about who gets to say what democracy is. Philosophers, historians, linguists, experts of some kind? Should we follow the current consensus? Some people might want to say, look, Rebecca, you know, I can tell you what democracies are. They're the countries that count as democracies today in the world.

As philosophers, we might want to say, well, what is it that makes those countries democracies? Can we separate this out from history? Can you have an ahistorical account of democracy? If you can't, does that mean that democracy is something that's contingent? Where do you… where does one start on something like this, do you think?

JOSH: Well, where I start, and here I have to admit that my training originally was not as a philosopher, but as a historian, so I get to start as a historian. But I think at least one perfectly plausible place to start is with the word. Where does the word come from?

Well, of course, it comes from the Greek demokratia, which is a combination of demos, meaning roughly the people, or some defined people within some defined territory, and kratos, which means strength or rule or power or, as I’ve argued, capacity to do things. So the core meaning of the word by the people who invented it was ‘people plus power’, or ‘people plus capacity’. And I think that's not a bad way to go.

I mean, it doesn't mean that the Greeks own the concept. Obviously we can take a word from a completely different area and redefine it entirely as we please. But I think actually we get quite a lot by starting with the idea of demos as people, and kratos as some kind of power, and then asking ourselves, how does that really work?

What are the implications of that? What are the, once again, conditions under which a demos would actually be the empowered agent. Such that we rule ourselves, rather than being ruled by a king or a junta or the wise or the meritorious or whoever it might be.

REBECCA: So actually that offers us a useful comparand for your opening definition. So we can compare ‘no boss’ with ‘people plus capacity’. And I think one thing ‘boss’ gives the implication of is it's suggesting something directional, I think.

JOSH: Quite right. Yes, exactly. So if you are to take the, basically, ‘you need a boss’ arguments about politics, you know, Thomas Hobbes being the great master of this. And Hobbes, you know, of course, one of the greatest political thinkers of certainly the Western tradition…

REBECCA: Of course. I mean, he's fantastic. He just happens to be wrong on almost everything. He's wonderful…

JOSH: Well, that's it. That's right. That's quite… so I suppose. Brilliant, brilliant argument, but in the end doesn't go through. But if you take Hobbes: Hobbes says that you really need a direction. There must be a rule over. That you always have to have, ultimately, a sovereign. And the sovereign must be in control of… all of the government, and in charge of those who are governed.

So there is always a who/whom. Who is running things, and over whom do they rule? So that's very directional. And democracy, in my view, basically, pushes back on that and says, no, there isn't a who, and we are not ruled over in that directional way. That rather, we rule ourselves, and so in a sense, it's omnidirectional.

Now, of course, there will always be some people that we designate as the officials who are going to carry out certain things. And they may have a certain authority and we have to obey whoever it may be — the people that we designate in official positions, but they are accountable to us. They're not our rulers. We are ruling ourselves, and we're delegating our authority to rule ourselves to particular people, contingently, based on good behavior and so on.

REBECCA: Excellent. I want to come back to that. Particularly this point about directionality. I think I want to ask you at some point around the kind of teleological nature, as I see it, of some of your writing about democracy, which isn't surprising because you're an Aristotelian.

JOSH: In a sense, yes!

REBECCA: In a sense! But I just want to ask another clarificatory question, about the situations in which democracy can obtain. So sometimes you get people saying things like: the British Labour Party is more democratic than the British Conservative Party because it has votes on everything. Personally, I always think of democracy being some kind of analogy there or it being some kind of use of quasi-democracy.

And that's because I have this, I think, quite purist view, that democracy is something that happens within a political society. I don't think just because you and I started with me giving you some options, therefore this podcast is democratic. Am I being overly precious there?

JOSH: No, I don't think so. I think that it's perfectly possible to think that you have democratic practices within organizations of various sorts. You could certainly see that a given organization might be highly hierarchical. In which you have, say, a corporation, in which the CEO is just simply the boss. The CEO is ultimately responsible to, say, the stockholders, the people who own… the ultimate owners of the company. Given that, the CEO has total authority to get rid of people he wants and do what he wants.

Whereas you might imagine then you have a partnership organization — lots of law firms are organized as partnerships and so on — in which a group of people can be understood as, in a sense, the citizens of the organization. And nobody within the organization has total authority over everybody else. You have to have some kind of a decision process, whereby those who are the citizens, those who have a full membership in, whether you do it by vote or some other way, determine the outcome.

So I think democracy doesn't have to exist uniquely in a state. It can be a feature of organizations. But I think it's most interesting to talk about at the level of the state, because then that's the ultimate, in a sense, structure, in which we might want to not have a boss. I might be perfectly happy to work in a firm that has a boss, and say, fine, you can order me around. But as soon as I get tired of you ordering me around, I'll just leave and go to some other place that I think has a nicer job culture.

Whereas it's much more difficult to leave your country, to leave the state in which you are a citizen. So I think talking about democracy at different levels is interesting, but ultimately I think we should sort it out first at the level of the state.

REBECCA: So I think two things in response to that. One, so let's think of an organization that we might not be so happy to think of as democratic, even if its practices seem to match some of these types of practices. So say you've got the murder company, and the objective of the murder company is to go around murdering people. But one day they decide the boss has got too much power. So they decide they're going to let the employees, including you know, the cleaners, the people who clean the guns, have a vote on who the next person is to murder.

I think there might be two problems with that. One, we might want to say something like, maybe democracy is something that only obtains when there are certain good goals in place, perhaps. But another thing we might want to say is, look, one of the reasons why democracy is important within political society, is because it pertains to certain kinds of rights we have, rights to have choices over how we spend our life. And those are particularly special when it's to do with contributing to the running of your political society.

JOSH: Right. So two things here. Is democracy necessarily linked to good ends? And therefore, we'd have to specify what good ends are. The murder company might believe that the people they're murdering are really wicked people and the world is better off without them. So they have these very… I could say they're wrong about that… but they might believe that that's the case.

So I think if you look at various states that we, I think, are going to probably have to agree, at least meet my definition of democracy. Often they do things that I wouldn’t think are good. They're imperialistic. They're colonialist. They engage in… look at the ancient Greek state that invented the term democracy. Athens, a slave society that denies citizenship to women… is very hesitant about giving citizenship to those who weren't born as citizens. All kinds of things that you might think are wrong, from my perspective. And yet to say that it's not a democracy, it wasn't a body of citizens ruling themselves, seems to be, to me, a mistake.

So I tend to separate democracy as collective self-government by citizens. Now, we're beginning to elaborate that definition a little bit. But that’s the, I think, alternative to boss rule, is we rule ourselves: collective self-government by those who we define as just citizens. And then we get into the question of how do we define that. We haven't gotten there yet…

REBECCA: There's a risk if we push it downstream on to citizen that then you get the political society of 100 people and two people count as citizens… But those two people get a say, and then do we want to count that as democracy?

Because I think two objections to ancient Athens qua democracy, in relation to slavery. One would be: sufficient people didn't get to have a say, so it doesn't count as collective self-governance. The second might be a more kind of... just a general idea that this is a society which is grounded on slavery, or that slavery plays such a big role, that therefore there isn't a sufficient atmosphere of participation or of political equality that manifests in this place. So that's a bit more of a wishy-washy criticism.

JOSH: Yeah, yeah, so as we continue to develop our definition, I would say that democracy is collective self-government by a citizen body that is large, that is beyond face-to-face, and socially diverse in some meaningful way so that we're not all the same.

REBECCA: You've got collective self-government of a large body that's socially diverse...

JOSH: …socially diverse in some meaningful way. Now, that doesn't mean socially diverse in every way we could imagine today. Social diversity…

REBECCA: Does that social diversity have to reflect the social diversity of the wider body within the polis or is it sufficient just to be diverse within itself?

JOSH: I think it's sufficient to be diverse within itself. So every… there is no existing, historically existing democracy in which everyone who was affected by the decisions of the citizenry had a voice in that decision. So that's one sort of idealizing theory of democracy, is democracy pertains when all those who are affected by a decision have a part in making that decision.

But when we think about the modern world, that would mean ultimately that in the case of powerful states like the United States, that every decision that is made must in fact be made by everyone in the world. Because when the United States goes out and does something, ultimately it ramifies over at least many of the people of the world. So at that point, democracy could only exist at the total global level. And that, I think, basically vitiates the entire notion of democracy.

So every democracy is exclusionary. That's one of the things you need to bite down on. And that’s… some of the books I’ve written say that there is always exclusion. There is always an us, and there are always people who are not us.

And indeed, there are always people within the bounded territory, which is ours, within the jurisdiction of the citizen body, who are not citizens. At a minimum, children. No one has ever said three-year-olds ought to have a vote. That's at least intuitively, I think, sufficiently implausible.

REBECCA: You do get those places where they have, what is it called, Demeny voting, where people vote on behalf of their children…

JOSH: Right. But there, that really gets sort of tricky, doesn't it?

REBECCA: Yeah, yeah.

JOSH: I have 12 children…

REBECCA: Pretty easy to game…

JOSH: Yeah, 12 children, and suddenly I have 12 times the votes that you do!

REBECCA: My kid is telling me that the marginal tax rate is really wrong!

JOSH: Exactly right. So I think that would… I think there are tricks that we probably don't want to introduce. That's why the sort of ‘one individual, one vote’ turns out to be one of the primary principles.

REBECCA: And of course, that's sometimes also used as a kind of shorthand definition for democracy too: one person, one vote. But I think some of this conversation, particularly around the social diversity condition, and also the point around children, brings us on to an almost prior question, which is why should democracy obtain?

So one answer could be that this kind of type of decision-making procedure in which you get socially diverse actors coming together, it has some epistemic power. We know that if you have a diversity of views, you can come to some better conclusions. There's also an epistemic argument about: we know our own needs and preferences better, therefore we should have a say in the decision-making that affects us. So that's one kind of argument. It's the epistemic value of democracy.

Another argument is something like, which you also touched on, this idea of we should have a say over the things that affect us. So yes, I agree that there are going to be some things that we can't have a say about that affect us even if we want to have democratic standards, because we live in a global world. That brings us on to, I think, something that joins these together is something around us as reasoning creatures.

So because we're reasoning creatures, therefore we can join together and make good decisions together. Because we're reasoning creatures, perhaps we have the right to make decisions for ourselves. It seems worse to impose something on a reasoning creature than on a non-reasoning creature. I mean, the answer probably is it's overdetermined, but do you have a preference, to use an apt term here, for the reason why democracy should be in place, if indeed you have a normative account in that sense?

JOSH: Yeah, yeah, I do. But before I say that, I want to say that when I think about democracy, and this is from this book on Demopolis that I wrote a few years ago, that I think that in order to get my definition off the ground requires that the citizenry agrees on this basic thing. And that is, we don't want a boss.

So if we, whoever we are, say we're happy with the boss, the emperor is divinely inspired or is wiser than we are, or the party is doing a very good job running things, and we're genuinely happy with that, I have no argument for that person. That I think is going to be, at least, very persuasive.

REBECCA: This is because you think consent is a necessary condition, or because you think it just doesn't work? Because there are lots of arguments today… we've tried — the Americans, you guys anyway — have tried to impose democracies on other places, and it doesn't work. Or is it because you think a requirement here is the consent of the actors who are bound by each other, or something?

JOSH: I don't even think we need to drag in the term consent. It's just a preference. People just simply prefer to have someone else running things because they think it will be better for them. And so, yes, you can say they consent to it or they affirm it or they just think that's a nice way to have things go.

Now, why are they wrong? I mean, because now we get into the idea, I think there actually is a normative argument, and I think that they, to my mind, they're wrong. Although I'm not certain enough that they're wrong that I would want to impose my view on them. I think they're wrong. And this is getting to the Aristotelianism. So Aristotle famously says that humans are political animals. And he defines why we are different from other kinds of animals in terms of basically three features.

One is that we are hyper-social. We only flourish, we only do well, we can only really even survive when we live in communities, in groups. And that's just true. I mean, that you look at human beings and we live in groups. It's not every primate lives in groups, right? Orangutans live, you know, quite separately: one orangutan per tree, more or less.

But human beings always live in groups. And we live in groups that are, Aristotle thinks, not only important because we provide goods, material goods, that we need to live well, but we provide together moral goods that we need to live well. How do we do that? Aristotle thinks that's because of these other special capacities that humans have that are just different from those of other animals.

The first is the use of reason, the capacity to then think through right and wrong, good and bad, as well as advantageous and not advantageous, right. So all animals can think about advantageous and not advantageous. They go for what is going to be good for them or they imagine is good for them, not for what's bad for them. Cows eat grass, not things that aren't good for them. But humans have this capacity to use reason quite broadly, for moral reasons.

And so the third thing. So we have hyper-social, we're reason-using beings, and we're communicative. We have language. We have very super-complicated forms of communicating our reasons, what we use our reason for, to one another, in order to live our hyper-social lives.

All right, so put together being hyper-social with reason-using, with communication, and it seems to me you've got democracy. If we’re each of us like that, if each of us are that animal, then we oughtn’t to be simply ordered around by somebody else.

REBECCA: I read Demopolis when it came out. I've reread some of it in preparation for this. But I do remember, I think, reading you as making this argument for the intrinsic value of democracy. Intrinsic value is a very hard thing to talk about because oftentimes it ends up slipping into instrumental value. But the intrinsic value of democracy is something like: because it enables us to exercise these core capacities of being human. These three that you talk about: reason, interpersonal communication and sociability.

JOSH: Yeah. Yeah. And I think that's just, if you think that in that sense, humans being, for Aristotle, animals like other animals, right? We have these special features. He thinks it's in some ways godlike, or it allows us to imagine what it would be godlike. But the bottom line is we're animals like other animals. And every animal, or at least let's say every mammal — because I can't even imagine the lives of insects and so on! But anyway, every mammal has certain capacities.

The exercise of those capacities, in a complete way, is at least part of the good of that being. That the exercise of the special capacities that make that particular species what it is, is part of its good. So we all have basic goods that we need as animals, you know. We need food, we need shelter, and so on. So that's just a given.

But when we have special capacities, like the use of reason, communication, hyper-sociability, then the exercise of those capacities is just a central part of our good. If we don't get to exercise those, we are missing out on some part of the goodness of being in existence.

REBECCA: And you can go as far as to say that when somebody imposes that bad thing upon you, they're doing something wrong. So if it's just naturally the case, if you're in a coma and you can't do those things, we can say it's bad. But if somebody is not allowing you to exercise those capacities, it's wrong. And this enables us, I think, to make a strong argument for democracy, even if we can't prove its fantastic results.

So there are all these theories: the democratic peace thesis, the ‘no famines in democracies’ idea, the arguments people make for democracy leading to economic growth, all kinds of arguments about which way the causal arrow flies. We can actually set those things aside, can't we? And contemporary criticisms, like: oh, but democracy brings bad results, it brings bad leaders.

If we've got this separate argument that isn't dependent on the good results of democracy, that gives us a really strong position to start arguing for its value.

JOSH: Yes, I think so. Now, once again, going back to what we were talking about earlier, if democracy means that we're hungry all the time, we're genuinely in fear all the time, then we might say, look, it's just… clearly there's something going wrong. Because exercising our basic capacities as the kind of being we are leads us to a position of being miserable or constantly in danger.

REBECCA: So that would tend us to think, therefore, of democracy in a slightly thicker way. So you've got the kind of thin conception, on which it's just a particular kind of decision-making procedure. Perhaps a decision-making procedure that pertains to particular kinds of decisions, whether or not we want to say it only happens within political situations or not. I know that you said that you can have democratic decision-making in non-political situations.

But I think, and this brings us back to this point about teleology… So, your fantastic thought experiment, Demopolis, which I want to talk about a little more in a moment, but this seems to be aimed at security, prosperity, stability, non-tyranny. Does that make it therefore a goal-driven order rather than a decision-making process?

JOSH: Yeah, well, I think it is, you know, ultimately. I mean, what I want to claim is that if people have, for whatever reason, this preference for not being ruled by a boss, which I think they have good reason for..

REBECCA: So minimally that has to be some goal or some agreement?

JOSH: That's right. That's right. So you've got that.

REBECCA: Some people want to say, can you vote away democracy? One argument against that would be to say, look, it just isn't democracy if you voted it away.

JOSH: That's right. Then you have said, you know, we're going to vote for establishing a boss. And then by my definition, no, then you voted for not democracy. Now, you might do that, but that's not…

REBECCA: Democracy no longer obtains.

JOSH: No, then democracy no longer obtains, exactly so.

REBECCA: Do we need to clarify, therefore? Do we need to qualify? Do we need to add to the latest definition I think we had, which was the collective self-government of a large, socially diverse body? Do we need to add anything in to recognize this, or do we think it's already inherent?

JOSH: Well, I think that we need to then think about the conditions under which that large body will be able to govern itself without an external boss. And this is where I think we get some of the basic features of what we tend to think of as liberal values, even without calling them values.

So you might say that now I think that, at a minimum, freedom of speech and freedom of association are going to be necessary conditions for a large socially diverse body to govern itself. Because if you as a citizen of this large body are not allowed to express your views, if you're not allowed to use reason and communicate your reasons to others, if I say, No, Rebecca, you're not! Then clearly you are not among those of us who are governing ourselves.

And if I say, you are not allowed to associate with others, or you're only allowed to associate with certain others, in the rest of your life, or in coming together to make whatever collective decision we're making. Then clearly once again: somebody's your boss! They said, you can't do this, and you can't do it.

So I think… you can say free speech is a genuine value. It's something we ought to intrinsically value for itself. But even if you don't say it's something I value intrinsically for itself, I think you can say it's a necessary condition for self-government. And if you say that, well, the goal is no boss, then you're going to have to say, well, you've got to buy into that.

REBECCA: So this seems to me clearly true, both that there must be some necessary conditions for democracy to be able to exist and persist, but also that free speech must be one of these things.

But you're famous for arguing that this set of things, these conditions, don't combine to create liberalism, or something like that. So you argue that democracy comes before liberalism, both conceptually as well as historically: so, democracy doesn't entail liberalism, it doesn't need liberalism, it can stand on its own, it's possible to have non-liberal democratic societies. Is that right?

JOSH: Yeah, I think at least it's conceivable. So I think when we look at ancient Athens...

REBECCA: A very Nozickian way of approaching it, conceivable rather than possible. I like it!

JOSH: [laughs] So, is Athens a liberal society? It certainly is a democratic society by my definition, despite its exclusions. Is it a liberal society? Some people have said it is, and it's possible to imagine it that way. The Athenians did begin to actually value free speech, not only recognize it as a condition for maintaining their citizen government, rather than tyranny of some sorts. So you can say that it was liberal, in that sense.

But it's not liberal in the sense of believing that there are intrinsic rights that humans have because of their humanity or because of their reason. The Athenians thought that the people who had free speech, and whose speech was protected against being encroached upon... They have a whole vocabulary for free speech in Athens that we don't have to go into. But that's for Athenian citizens. It wasn't a right that is intrinsic, inalienable in some way for all people. It was for Athenian citizens. So in that sense, you could say it's illiberal. They don't have the conception of universal human rights.

And if you think that without universal human rights, that liberalism really is an empty concept, then you can have a democracy. It's not illiberal. That's the thing, that there are all these people in Hungary, and so on, who claim that that their democracy is illiberal: it is actually against liberalism. I think that's the wrong way to think about it.

But I think you could have a democracy that is not liberal. At least in so far as it doesn't bring in those very important concepts — whether we think they're metaphysical or otherwise — of human rights, as opposed to civic rights. As opposed to the kind of claims that you have on your fellow citizens because you are a citizen of this democracy. It's quite different to say that I have claims on my fellow citizens and they have claims on me, I have duties to them and they have duties to me, rather than I have duties to those that are human or those who have reason.

REBECCA: So certainly when I read your Demopolis book and some of your other writing, I think you rely on quite an expansive notion of liberalism. So one of these things that you see as a necessary feature in the kind of liberalism you're talking about is quite a modern conception of human rights, universal human rights. You also talk about distributive justice. You talk about modern conceptions of religious pluralism.

So somebody might say, OK, Josh, so you think that democracy comes before liberalism because you think liberalism is too burdensome. Is there a more narrow conception of liberalism that you might think is almost kind of baked into democracy, or obtains within those preconditions? I'm thinking of something like a narrow Lockean type liberalism. So, for instance, I have this quite heterodox view that you can have a coherent Lockean liberalism that doesn't rely on theological premises. Luckily, Locke argues everything in such a million different ways that I think you can build that.

JOSH: Separate that out, yeah.

REBECCA: And also if you have a narrower conception of rights — it's not the kind of modern, very expansive notion of human rights. Would you change your position a little if it were a…

JOSH: Yeah, so I think that liberalism, like democracy, is one of these terms that we can define a whole range of different ways. And this is why I think that people who have… you know, serious scholars have said Athens is liberal. There’s reason to think because they've got free speech, they've got basic conceptions of immunities against certain kind of treatments, and so on.

Not to get too deeply into Locke, which you know much better than I do, but Locke does believe in natural rights…

REBECCA: Yeah.

JOSH: He does think that we have certain rights by dint of our humanity.

REBECCA: You could read nonetheless his conception of justice in a really narrow sense of just freedom from arbitrary decision making.

JOSH: Yeah.

REBECCA: OK, I'm probably narrowing down too much now, but I feel like I could construct some argument on which the conditions you require in political society for democracy to obtain are things that I could call liberalism under a narrow Lockean…

JOSH: Yeah, I think that would make sense. So I think that the question of liberalism and democracy, the reason I wanted to separate them out, is because I think that there's a tendency to say that democracy entails a very broad group of commitments to universality, of a wide range of things that we designate as rights. To a level of redistributive justice that might be ideal, but it's very difficult to attain, and so on. So I wanted to say that you can have democracy as collective government by citizens, without buying into all of that.

REBECCA: Regardless of how it cashes out, it also just allows us to isolate out democracy and talk about its value. Because even if you say, look, these conditions that need to obtain count as liberalism, you still want to say liberalism is something different from democracy. It's playing a different role. These are different ways political societies are, even if they do tend to come together.

JOSH: Yeah, yeah, indeed. And I much prefer it when they do come together. So I want to live in a liberal democracy. I don't want to live in classical Athens. I'd rather live in a liberal democracy.

REBECCA: Of course. It also does strike me that while your argument, which I love — I love your book, and I think it's a very compelling argument, even though I do think I take a narrower conception of liberalism more generally than many people today. I'm not a Rawlsian. It does strike me that while you make this novel argument for democracy as separate from liberalism… Just in the everyday, when you're talking to your friends, they're going to have no problem at all with describing somewhere like Hungary as an illiberal democracy. You gave that example. I was talking to a friend about this yesterday, and he also mentioned El Salvador as an example.

So it seems in more common parlance that people do separate out those two things. They want to have these two axes. You have the liberal/non-liberal, and you have the democratic/non-democratic. It's just within political philosophy and political theory, that maybe because we've expanded liberalism thanks to Rawls, that this problem has arisen. And then we can't talk sufficiently clearly about democracy, which is why we need your book to remind us of the particular value of democracy.

JOSH: Yeah, good. I mean, the thing I really worry about this illiberal democracy business is that Viktor Orban and the other self-conscious illiberal democrats, are quite happy to get rid of things like free speech. Oh, that's just liberalism! We don't need that! So they reduce democracy to decisionism.

So they say that once you have a majority that votes for a certain thing, whatever they vote for, is perfectly legitimate. So if they vote to restrict free speech, that's fine. My thought is that, no, there's some point in which you eliminate, through this.. ultimately not even democratic approach to illiberal democracy. Because it basically says that the only thing that democracy is, is a decision mechanism, whereby the majority legitimately imposes its will upon everybody else, whatever that will happens to be.

REBECCA: And it binds them forever.

JOSH: It binds them forever.

REBECCA: Because another competing ordinary definition of democracy could be something like: knowing you can vote for the opposition, and that the opposition will get in if they get voted for. Something like that.

JOSH: Yeah, so I think the worry is that in this kind of decisionist conception of democracy, those who are not in the majority are simply wrong. And they've been demonstrated to be wrong, and the only proper thing for them to do is accept their error, and acknowledge the rightness of the majority's decision.

That's exactly what Jean-Jacques Rousseau says. That's the general will. The general will is established by, revealed by, the majority decision. And all of those who were not in the majority must now acknowledge that their will was not the general will, which is always right, in Rousseau's vision. And they will then immediately accede to the general will. And so that becomes… there's no way outside of that, at least until next time we get together and the general will turns out to be something else.

But it seems to me that's really the wrong way to think about it. This is strongly decisionist. The mechanism of the majority vote is what establishes, in an authoritative way, what is correct for us all to do, and we must all then acknowledge the correctness of that view. And if we don't acknowledge it, then we're traitors, then we're treasonists, and we ought to be reeducated or eliminated. And that's where I think you get into sort of the terror of genuinely… I mean that's if you want to talk about illiberal democracy, democracy that rejects liberalism. That's where I think it goes.

So that's very different from what I see as what's going on in Athens. And that's why free speech, free association, the possibility of continuing to believe that you were right, even though the majority voted otherwise, and even though okay that's now the rule and I'll have to obey the rule. But I still will continue to, as it were, be in opposition. And perhaps attempt to work with others in opposition to ultimately change the rules and align it better with what I think is the correct outcome. So all of that is possible within my democracy before liberalism. It's not possible within these forms of fundamentally illiberal democracy.

REBECCA: This also brings us on to some more practical questions about how democracy is cashed out, how it should be manifest. But before I do that, just briefly, we should go back to our definition we're at, at the moment, which is the collective self-government of a large, socially diverse body. Do we need to add something in about the conditions that are required for it to obtain, or is that sufficiently separate from the work that a definition should do?

JOSH: Well, I think that once you have your core definition, then if you're interested in practice in the phenomenal world, then you need to ask…

REBECCA: I’m a philosopher, Josh… the phenomenal world…!?

JOSH: [laughs] So what would it really take for this definition to be manifest in the world that we live in? And manifest in a way that could pertain over time? So democracy isn't just something that's happened once upon a time for twenty minutes.

REBECCA: It must persist.

JOSH: The form of social organization for a large group of people over time. So something like stability becomes at least a part of what we should be talking about. And that really gets into these conditions. So you say free speech, free association. And then I think the third important one is that there's some level of equality, or at least political equality, so that we get back to our ‘one individual one vote’. So you don't, as a sort of super voter, get to have a thousand votes to my one. Once again, we’re not really doing it together…

REBECCA: What was it John Stuart Mill wanted? If people knew the rule of three, they got an extra vote or something…

JOSH: That's right. Yes, that's right. Or if they just had a degree from the right university.

REBECCA: Yeah.

JOSH: So I think these are… the basic political equality. And then you begin to then think further about what kind of material conditions of life are going to be necessary for people actually to act as citizens. To be able to use their reason, communicate to one another about conditions of collective life that are beyond just simply survival.

REBECCA: So this brings me to… sometimes people want to reduce democracy down just to voting. They particularly might want to reduce it down to voting once every four years, once every five years, for a ruling party or a president. This seems like a very denuded understanding of what it is to act democratically.

JOSH: Right.

REBECCA: Not least because, as you say, you need to be able to reason on stuff. If you need to be able to reason on stuff, you have to be able to partake in things. There have to be certain conditions, again, that obtain. If you don't have a free press or at least sufficient information, you can't choose who to vote for. You might also want to say that within the set of things that means you're acting democratically, or if you want to go further and say within the set of political rights that need to be recognised for you to be in a democracy, you might want to say you also must have the ability to run for office.

JOSH: Yeah, if basically I am denied the chance at taking my turn at being in a position of authority, accountable authority, then I'm not truly equal. I'm not really a full participant in the self-government. Those who have the right to, or the ability to run for office, are in some ways ultimately my boss. They're always going to monopolize the positions of authority. And since they have the capacity to do that, if we assume that we're not all fully altruistic, my guess is they'll probably do that in their interest and not my interest.

REBECCA: That also brings us on more explicitly to the obligations that come with being a democratic citizen. So maybe, to protest, if you think that a bad law is about to be enacted. To run for office, if you think that you have the right skills and the right knowledge.

JOSH: Yeah, I think that democracy is actually quite demanding. Turning over the business of ruling, making decisions, carrying them out, doing what's necessary to sustain, let's say, a decent level of welfare and security, takes time and effort. So there's reasons that peoples have been quite content to turn over the running of things to a boss.

REBECCA: They want to delegate, because the work is hard. The work is hard!

JOSH: That's right.

REBECCA: A lot of people like having a boss because then they don't have to be making hard decisions. They don't have to be telling other people what to do.

JOSH: That's right, exactly so. So I think that part of taking on the idea that yeah I don't want a boss, is there's going to be some real costs to that. And that you have to sustain that, if you really believe that that's important, if you think that you're getting maybe intrinsic value from being a democratic citizen. You have to realize that gaining that value is going to come at some cost in time and effort.

You could be doing other things. You could be playing video games, instead of going out and trying to convince your fellow citizens why it would be better to do it's not that… why the marginal tax rate should be higher or lower!

REBECCA: [laughs] This reminds us then that collective self-governance does mean being a boss over other people. I often think that the thing that describes me the best in terms of my preferences, how I want to live my life, is I don't want anybody to be my boss and I don't want to be anyone else's boss. But when you're a member of a democracy, effectively, you do become other people's bosses.

And if it goes to the extreme, you get someone like Robert Nozick, who makes, in his Demoktesis argument, why wouldn't you just give up ownership of yourself to have a little bit of ownership of other people? I have to say, I always find that a very strange way of thinking about democracy. But he does touch upon this point, that on some level, we all need to be a little tyrant. Is that true?

JOSH: Yeah. Well, at least we have to recognize that no boss but ourselves means that we are our own boss.

REBECCA: But also on some level, each other’s, because we're doing it collectively.

JOSH: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And that there has to be a decision mechanism, right? So you can say there's a majoritarian decision mechanism, or maybe we'll do things as much as we can by lottery, or we'll slide a drive towards consensus. But then there's the worry that we're going to be simply pushing people to consent. So, yeah, there's going to have to be a decision mechanism by which we set a rule, and that rule will be constraining, right? That rule will be coercive.

REBECCA: And we'll have to be party to that. We'll have to be party to coercing other people. That's suddenly not sounding quite so attractive, particularly for those of us who are hardcore liberals.

JOSH: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

REBECCA: So what's the alternative…

JOSH: Yeah, well, the alternative is to have a perfectly benevolent boss who seems never to coerce you, but of course coerces you all the way down.

REBECCA: Unfortunately that leads me, therefore, to have to say the really obvious thing, which is — I think it was Churchill — that maybe democracy is just the least bad type of government.

JOSH: Yeah, but then if you're an Aristotelian, you begin to then go back to: but remember the things that you are actually gaining from that.

REBECCA: Exercising your core capacities!

JOSH: Exactly right. So it's not just that you're having to do this because everything else is bad. You're actually doing this in a way that is genuinely good for yourself. And if you're genuinely doing it with others, we are doing it in ways that are good for ourselves. So, yes, we have to set rules. Yes, there is coercion ultimately involved. But on the gain side, there is something of genuine value that we are actually being the beings that we fully are to our fullest extent. And I think that's worth putting on the benefits side of the equation.

REBECCA: I like that. It's a very rich and happily hopeful idea of democracy. It's not just we won't be killing each other, the Hobbesian kind of bargain. It's we can actually exercise our core capacities as individuals and do good for each other such that we have a rich society down many lines.

JOSH: Yeah, yeah. And I think that conception allows us to recognize that self-interest is certainly part of what we are as beings. We want to flourish individually, but we only flourish individually when we recognize that our good is intrinsically bound up with the good of those around us.

REBECCA: That's right. My good isn't Rebecca good. My good is human good. I share it with you, I share it with everyone else. That's why I have my interests and my rights: for the same reason that you do. And democracy manifests that as a political… not just a process… I think you're right, as an action, as a way of living together.

JOSH: Yeah, that's right. So I think that really is true. It doesn't turn into a kind of strong form of altruism. It doesn't mean that the right thing for you to do is to sacrifice your good for the good of others… that trying to get something good for yourself is somehow a kind of selfishness that you ought to try to extirpate.

Rather, you just see that your good is intrinsically bound up with the good of others. And therefore you cannot really do well for yourself unless you are engaged with doing all that kind of good for others as well. It's just that, yes, your self-interest, your narrowest self-interest, is inextricably bound up with the interests of others.

REBECCA: Love it. So we’d better wrap up. Let's return to where we're at with our definition. We have gone from no boss — the shortest ever, syllable-wise, and on other counts, definition of democracy — to something a little longer, which is collective self-government of a large and socially diverse body. I think we decided we could keep the conditional matter external to that.

Anything else you think we need to add in at this final moment, Josh?

JOSH: My own goal in thinking about democracy is to keep it as lean as possible. To make it as amenable to a wide range of possible forms of social existence. To people that have different conceptions of the ultimate good, or no conception at all of the ultimate good. It seems to me that that definition allows us to see more deeply than other definitions why democracy is intrinsically bound up with the kind of beings that we actually are. And that is the core Aristotelianism of a lot of my arguments.

REBECCA: It's also very conceptually valuable. It enables us to define it in such a way that we can demarcate, in such a way that we can apply it across different historical situations. That seems to me valuable in itself.

JOSH: I hope so.

REBECCA: Well, thank you so much, Josh. I've really enjoyed this. Thank you for being my second guest on this podcast. I've really enjoyed our conversation.

JOSH: It's been delightful. Thank you very much, Rebecca, for leading us through it.

REBECCA: Thank you so much!