five top things i've been reading (eighth edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

TLDR:

A Theory of Justice, John Rawls

‘Introduction: Modern Moral Philosophy, 1600-1800’, Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy, John Rawls

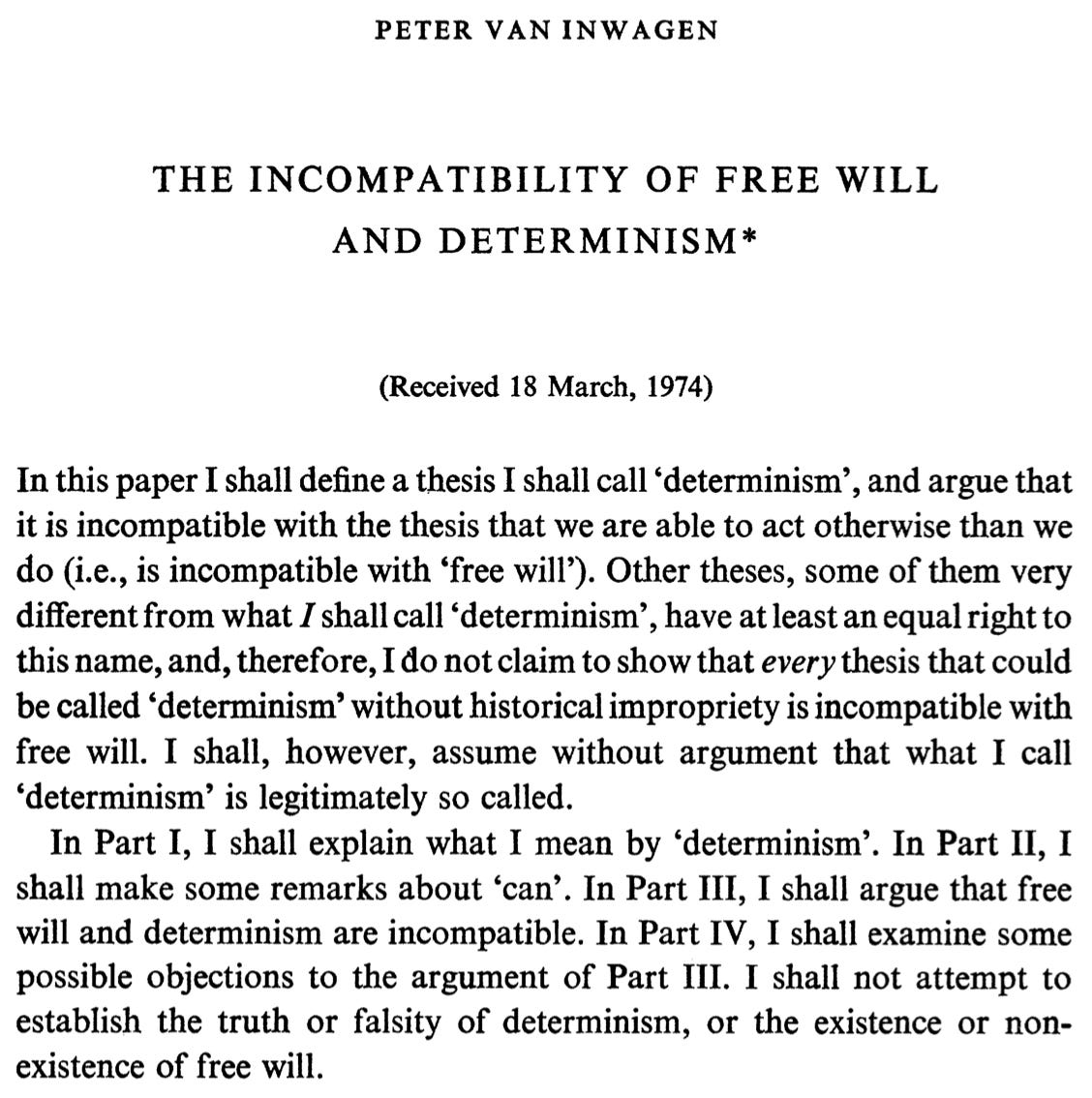

‘The Incompatibility of Free Will and Determinism’, Peter van Inwagen

On the Calculation of Volume II, Solvej Balle

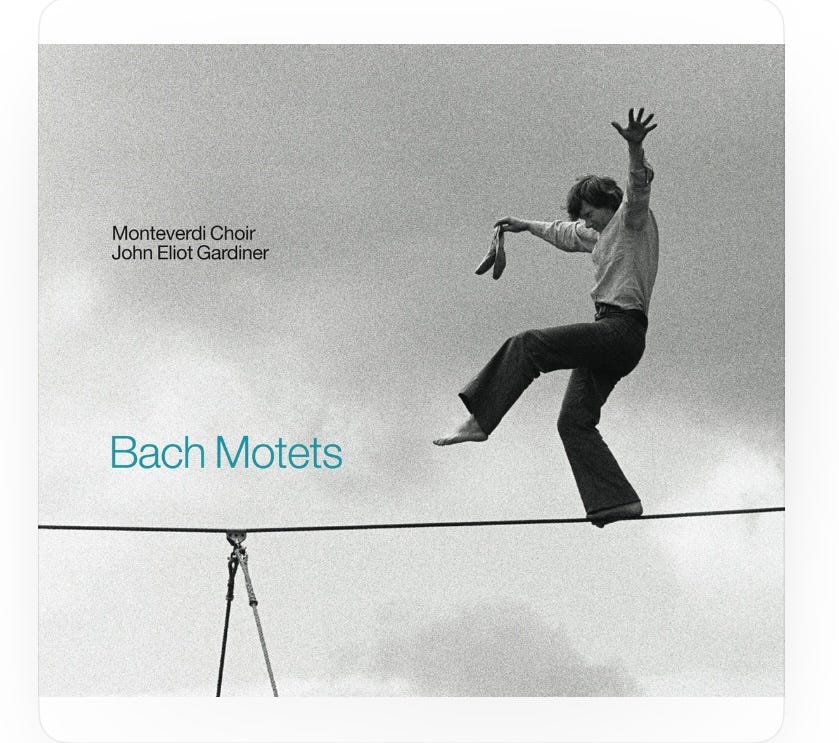

Komm, Jesu komm, Monteverdi Choir, conducted by John Eliot Gardiner, SDG

This is the eighth in a regular Sunday series.1 As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond ’things I’ve been reading’, towards the end.

1) This weekend, I’ve been reading works by John Rawls, because I’m giving a talk about him tomorrow. As part of this, I read through (much of) A Theory of Justice (1971), for the second time in my life. That is, while I often return to sections of this book, it’s been a long time since I read it in order. My main takeaway, on having done so, is that I’ve become too uncritical, over the years.

I don’t mean I’ve persuaded myself into agreeing with everything Rawls says! I’ve retained problems, in particular, with the ‘difference principle’. This is Rawls’ famous idea that the “higher expectations of those better situated are just if and only if they work as part of a scheme which improves the expectations of the least advantaged members of society”. Of course, it’s important to note that this principle only comes into play after Rawls’ prior conditions of ‘equal liberty’ and ‘fair equality of opportunity’ have been met. Nevertheless, it effectively entails pretty serious economic redistribution.

The first problem I have with this approach tracks Nozick’s concern about ‘patterned theories of justice’. In Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974), Nozick argues that principles of economic justice that follow ‘patterns’ (i.e., maxims that typically follow the ‘from each: to each’ format, and that guide redistribution in line with values such as desert, efficiency, and need) are incompatible with individual freedom. Patterned approaches, Nozick shows us through his Wilt Chamberlain thought experiment, lead to endless interventions in the lives of individuals. And whilst Rawls might be correct that most people would buy the idea of the difference principle (if you didn’t know anything about how advantaged you would be in a society, mightn’t you want to insure against the badness of being the least advantaged?), it’s hard to see how this principle could be put into practice without a load of persistent intervention. There’s a separate concern that bothers me almost as much, however. Mechanistic problems aside, I’m generally happy with the idea of paying tax to fund a ‘social minimum’ — in the sense of a means-tested safety net, focused on ensuring nobody is left unable to meet their objectively-determined basic needs. Yet, as clever and as nice as the ‘difference principle’ might sound, the relativistic nature of its ‘least advantaged’ targeting means that absolute need neither directs nor constrains the equation.

Beyond these ongoing concerns — and the stronger concerns I have with his later works — I’ve come to love Rawls, however. I’ve long had the view that if there are any philosophy geniuses, then Rawls is definitely one of them. After all, he addresses the big important questions in valuable innovative ways, and he drew political philosophy up out of the depths of insidious consequentialism and vacant intuitionism. I even like his dense writing style! Having revisited ToJ this weekend, however, I’ve concluded that at least some of my love for Rawls has been a reaction to the ridiculous Rawls-bashing that goes on these days. Driven largely by purposeful misreadings (or non-readings) and the confused motivations of virtue-signallers, this bashing of Rawls seems so endless and so wrong that, often, I’ve felt the need to push his best features. Neither his genius nor his victimhood make him correct, however. And when it comes down to it, that’s probably the most important thing.

2) Today, I also read some of Rawls’ Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy (2000) — a big book that shares a late version of the undergraduate course he taught at Harvard. I particularly enjoyed the introductory section of this book, in which Rawls compares the context of Ancient Greek moral philosophy with the context of modern moral philosophy (c.1600-1800). The Ancient Greeks, on Rawls’ account, were left free to ask ‘How should one live?’, unencumbered by an overbearing religion focused on maintaining personal devotion. Whereas, the ongoing influence of top-down medieval Christianity, alongside the post-Reformation rise of alternative religious groups competing to save everyone’s souls, left modern moral philosophers asking ‘How should one live with people from other authoritarian salvationist religions?’. Rawls doesn’t just set out historical arguments about the “nature” of different moral philosophical traditions, however. He also gives us plenty of interesting takes on the ideas of particular moral philosophers (most notably Hume and Kant), and a nice little essay on the philosophical value of the history of philosophy.

3) As part of my ongoing project of reading classic twentieth-century philosophy papers, this week I returned to my friend Peter van Inwagen’s ‘The Incompatibility of Free Will and Determinism’ (1975). As you might guess from its title, this is a paper in which van Inwagen argues that free will and determinism are incompatible — a position that non-philosophers might be surprised to learn has become unorthodox! By ‘free will’, van Inwagen broadly means having the ability to act “otherwise than we do”. In other words, the idea that, at this particular point in time, and of your own volition, you could’ve been doing something different from reading my Substack. Sad! And by ‘determinism’, van Inwagen is referring to the idea that the current ‘state of the world’ (including you reading my Substack) had to be the way it currently is, because it’s the only possible result of the laws of physics acting on previous states of the world. Rather than getting into the details of van Inwagen’s argument about the incompatibility of free will and determinism, however, I’ll flag three other things I like about this paper.

First, I admire the move that van Inwagen makes by ruling out matters of voluntary behaviour to the remit of the ‘laws of physics’. These laws have similar breadth to what other people call the ‘laws of nature’, he tells us, so we shouldn’t take them to ignore matters of chemistry or biology. But they are also separate, he continues, from anything we might think of as ‘psychological laws’. This enables him to accept that “it may be that some version of determinism based on voluntaristic laws is compatible with free will”, which is a pretty audacious move in a paper arguing for incompatibilism! It also helps to focus his paper, however, and shows us the important role that tight definitional work can play in winning an argument.

Second, I like many of the clarificational asides that van Inwagen makes in this paper. Take, for instance, the parenthetical remarks appearing in the following sentence: “We shall find this new idiom very useful in discussing the relation between free will (a thesis about abilities) and determinism (a thesis about certain propositions)”. This sentence comes at the end of the section in which van Inwagen introduces his ‘rendering propositions false’ idea. But, regardless of whether you think it’s useful to translate claims about abilities into claims about ‘rendering propositions false’, and regardless of where you stand on van Inwagen’s incompatibilist conclusion, the relation between free will and determinism that arises from the neat clarifications found in these parentheses is worth thinking about, in itself.

Finally, at the end of the paper, van Inwagen offers a guide to attacking his argument: “The most useful thing a philosopher who thinks that the main argument does not prove its point could do,” he says, “would be to try to show that some premise of the argument is false or incoherent, or that the argument begs some important question, or contains a term that is used equivocally, or something of that sort.” This is a useful summary, with much general application value. Beyond that, however, the general beauty of van Inwagen’s linguistic and rhetorical style is neatly emphasised by the sentence that follows: “In short, he should get down to cases”.

4) Last week, I wrote about Solvej Balle’s On the Calculation of Volume I, which is a novel set almost entirely on a single day — a day experienced hundreds of times by its protagonist, Tara. It’s also the first novel in a set of six. This week, I read the second. As with its precursor, Volume II is full of beauty and substance. I particularly liked its discussion of the emotional value of the seasons, its descriptions of fruits and vegetables, and its increasing focus on what a ‘Groundhog Day’ premise means for the relation between time and change. I wrote last week that I interpreted the first Calculation novel as a comment on the debate about the independence of time; the second left me feeling vindicated in this.

5) Komm, Jesu komm is my favourite of the Bach motets. I listened to my favourite recording of it — John Eliot Gardiner conducting the Monteverdi Choir — several times this week, as I do most weeks.

Again, I’m publishing this after midnight UK time, but it’s still Sunday in some other places.

Rawls, in my estimation, suffers from the analytic delusion that it’s possible to change just one thing: that wealth redistribution can be assessed solely on whether it helps the “least advantaged” by eliminating their needs, as if that were its only effect. But a world without need is a world in which no one needs you. So you could reframe his central question as: would you rather live in a world in which other people needed you or one in which they didn’t?