five top things i’ve been reading (fifty-eighth edition)

the latest in a regular ‘top 5’ series

Best of Moltbook, Scott Alexander

When Misinformation Kills, Peter Singer

Special Report: The night everything at DCA finally went wrong, Will Guisbond

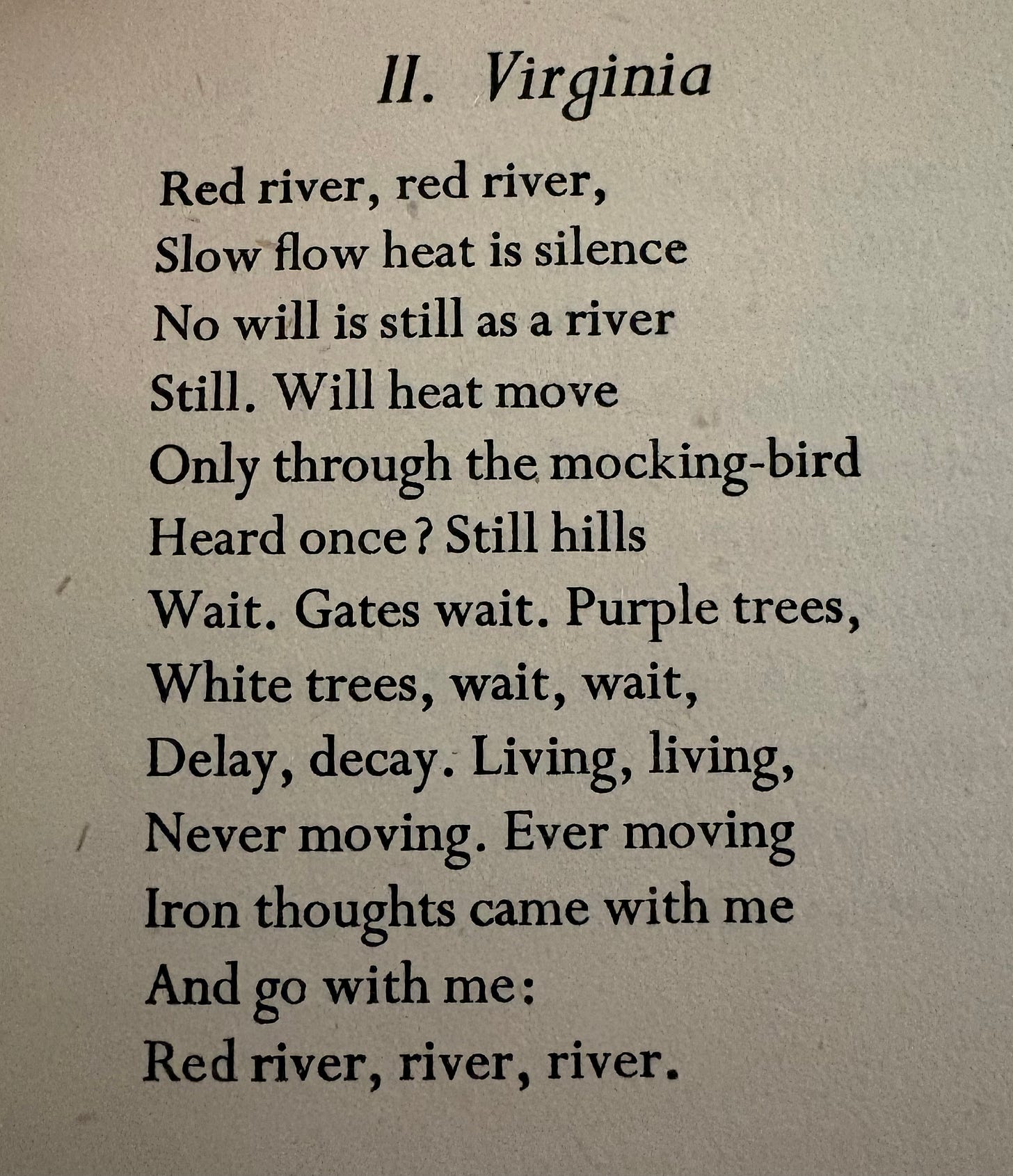

Virginia, T.S. Eliot

Severance, season 1

This is the fifty-eighth in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) On Substack this week, I really enjoyed Scott Alexander’s energetic tale of the Moltbots having a happy old time on Moltbook. Okay, I’m already on the record criticising this piece for its philosophically loose language use. I wrote:

“What can it possibly mean for something to make the Moltbots happy, if the Moltbots are not the kind of thing that has internal awareness? Okay, I’m reading extensive implicit claims into what Alexander is saying here, to come to this conclusion about his position! And again, there are important long-running philosophical debates about whether, for instance, dogs can be happy in the ordinary sense of the term.

But how could you be happy without being alive? Does Alexander really mean that the Moltbots are alive, when he describes them as “lifeforms”? That they are living things, in the sense that we ordinarily understand the term ‘living’? And even if he does believe this astonishing thing (!), then how could the Moltbots be happy without having any of the interiority that only phenomenologically conscious kinds of living things can have?

In other words, it’s hard not to come away from the Alexander extract thinking that Alexander is saying something like: ‘Hey, even if the Moltbots have no inner life, Moltbook makes them happy!’. Or less strongly: ‘Hey, I don’t need to get into discussing the “consciousness or moral worth” of the Moltbots, or whether or not they are able to “mean” anything they write, or anything like that, to be able to conclude that something can make them happy’.1

This is bizarre!”

But it’s a fun piece on a fun topic. A fun topic for now, at least.

Another piece I enjoyed on Substack this week was Michael Pakaluk’s reflection on Elizabeth Anscombe. Pakaluk’s focus ranges from Anscombe as a subject of boycott, to Anscombe on when the Virgin Mary became a zygote, to Anscombe as a rigorous respondent:

“At this Anscombe bristled and treated him harshly. What do you mean that there is a deterministic chain? Have I asserted this? “No, but of course there is.” On what basis do you assert such determinism? “Each stage or phase follows upon the other by laws which are deterministic. This is obvious. You can find it in any textbook of human embryology.” Name me the textbook you have in mind which says this.”

A third piece I enjoyed on Substack this week was my Mercatus colleague Patterson Beaman’s discussion of the Counter-Strike 2 skin market. “The what market?”, you ask, concerned! Don’t worry. The skins in question are just “cosmetic modifications to weapon aesthetics in one of the world’s most popular competitive first-person shooter games”. Though it turns out that trading these skins is a serious business. I have zero interest in online shooter games, but I like the way Patterson uses his analysis of this multi-billion-dollar digital market to provide explainers on broader matters of pricing.

2) I’ve written here before about how I sometimes strongly agree with Peter Singer’s conclusions, even though I think he’s guilty of propagating bad moral theory on a grand scale. So I agree, for instance, with Singer that industrial factory farming is abhorrent. But I do so without needing to give an inch to his consequentialist reasoning. Indeed, I agree with Singer’s conclusion that industrial factory farming is abhorrent, confident in my view that his consequentialist reasoning has no more capacity to respect the rights of animals than it has to respect the rights of humans.

Singer’s most recent Project Syndicate piece, When Misinformation Kills, doesn’t really bring us into the realm of debating moral theory, however. It’s a pretty basic discussion of the clear-cut danger of spreading bad information about vaccines. As Singer tells us, vaccines are “among the most extensively tested medical interventions in history”. And as he discusses, vaccines save countless people from easily avoidable pain and death, every year.

A deeper question that Singer’s piece provokes, however, is how we should respond to the fallibility of scientific enquiry. Singer contends that:

“In a free society, individuals may express their unfounded opinions about vaccines, knowledgeable scientists can rebut them, and public-health officials should examine the evidence and act accordingly. In rare cases, views opposed to a scientific consensus will turn out to be true and become a new orthodoxy.”

Except, of course, when we look across human history, it’s not just rare cases, is it? Many of the longest-held and strongest-held scientific consensuses have fallen across the years. An easy way that Singer could’ve bolstered his argument, therefore, would’ve been to emphasise that, at least in modern times, humans keep on getting better at science. Another, more important point he might have noted — something that consequentialists often seem to forget — is that there’s a crucial difference between strength of consensus and strength of argument.

3) One of the best pieces of science writing I’ve read recently was Will Guisbond’s report on the horrific collision that took place last year between a commercial jet and a military helicopter in the sky above the Potomac. Guisbond carefully, and largely non-sensationally, advances his case that the incident “was the predictable outcome of a deteriorating system that had been flashing warning signs for years”. Such tragedies can be hard to think about, but well-argued readable analysis pieces like Guisbond’s sometimes prove essential to holding lax actors to account.

4) Perhaps the best poem I read this week was this (below) astonishing T.S. Eliot reflection on the state in which I live. I also just started reading The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath — so far, this mostly consists in reflections on her dates with a series of very American college boys. Maybe I’ll write about it next week.

5) A few days ago, I finished watching the first series of Severance. As with Pluribus, I initially gave up on this show about 30 minutes into the opening episode, only to return to it months later and persevere.

Overall, I found Severance more philosophically interesting and coherent. And, although much of Pluribus was pretty compelling, I thought it really flagged towards the end. Whereas the final Severance episode was so tight and tense I almost couldn’t watch. The ticking in the background!

These shows have largely been wrecked for me by Solvej Balle, however. The world Balle creates in her On The Calculation of Volume novels — with its similarly central philosophical puzzle, and its similarly central set of isolated main characters — is just so much more complex, yet so much better cashed out.

My piece has the following footnote at this point: “Alexander’s implied conflation of whether a Moltbot can ‘mean’ something it says, and whether or not the things the Moltbots say are ‘meaningful’ (or whether or not the Moltbots themselves are meaningful) is also loose and unhelpful! Also, I won’t get into this here, but I’ve written several times previously about the tricky matter of AI individuation: I do not currently believe that AI is ever instantiated as an individuated thing, and this strengthens my belief that AI is not conscious.”

Thephilosophical critique of Alexander's Moltbot piece is really sharp here. The question of whether something can be 'happy' without phenomenological consciousness cuts to the core of what we're really debating with AI. Had a conversation with a friend last mnth who insisted ChatGPT 'understood' his problems, but couldn't articulate what that understanding actually meant beyond pattern matching.