five top things i’ve been reading (nineteenth edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

TLDR:

Joseph Raz 1939-2022, John Finnis

The Politics, Aristotle

The Prague Orgy, Philip Roth

Pierre Boulez Was a Titan of 20th-Century Music. What About Now?, Joshua Barone

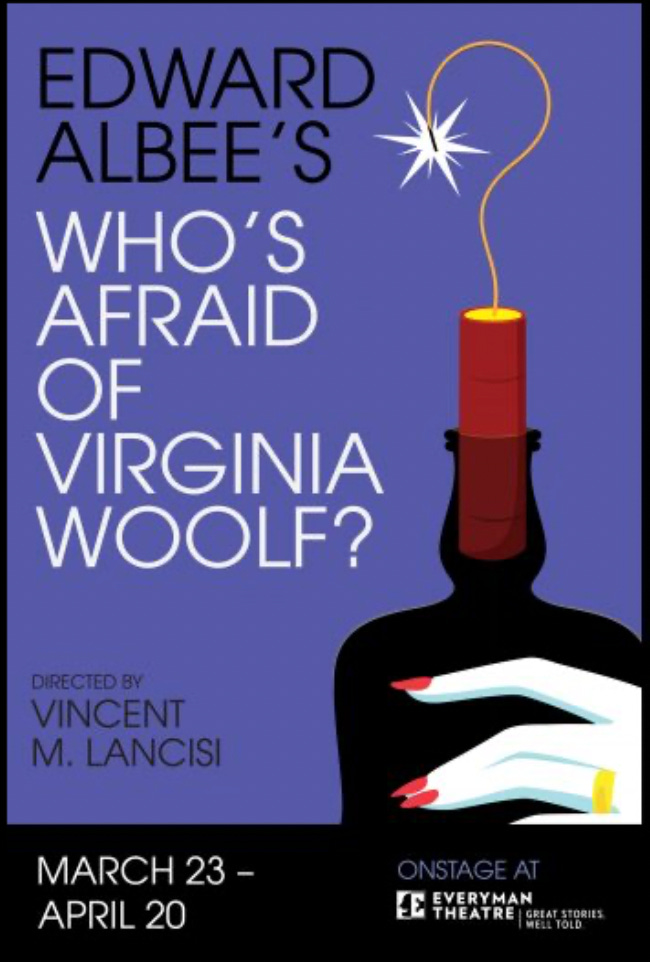

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Everyman Theatre, Baltimore

This is the nineteenth in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

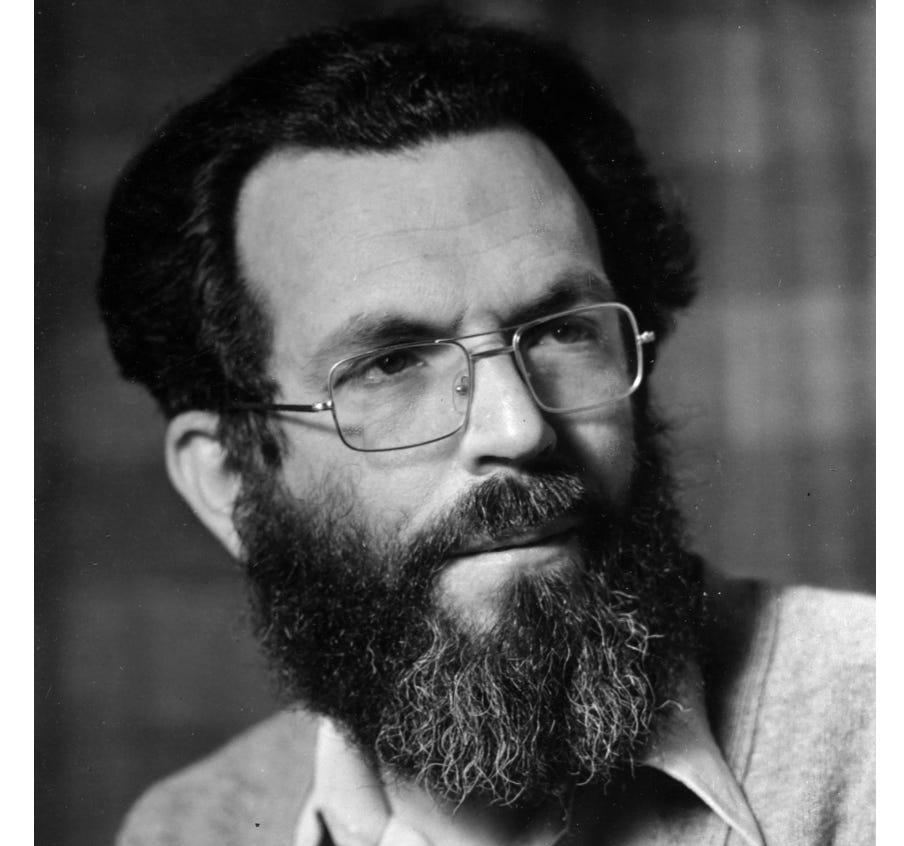

1) This week, I enjoyed reading John Finnis’s new ‘biographical memoir’ of the late Joseph Raz. Finnis focuses on Raz’s intellectual development in Haifa and Oxford, the over-reduction of Raz to unhelpful philosophical stereotypes including ‘legal positivist’, and Raz’s most important works and ideas. The more biographical sections of Finnis’s piece have quite an archaic style, but it’s a good read, as well as a comprehensive one.

On my view, Finnis and Raz are two of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century. Not only do they advance important arguments about important moral and political matters — in Raz’s case, particularly autonomy and authority, and in Finnis’s, natural rights and the common good — they generally do so clearly and compellingly. Nonetheless, weaker claims affording them this kind of status solely within the field of contemporary legal philosophy (a field they both helped form) are more common. In Finnis’s case, oversight is often related to his illiberal views on homosexuality. But rather than getting further into general assessments, or the risks of identifying philosophers by their worst arguments, I thought I’d take the opportunity to mention my favourite Raz argument.

My favourite Raz argument is the ice cream argument. This is the argument, advanced in The Morality of Freedom (1986), on which consequentialist reasoning is bad and wrong because it can lead to “absurdities such as the approval of the murder of an innocent healthy person in order to obtain ice cream”.1 This conclusion depends on the idea that, on a hedonistic consequentialist account, a sufficient amount of happiness would eventually be derived from people obtaining ice cream that this would not only justify, but would require, a murder to be committed, “if that [were] the only way to get the ice cream”. It’s a great argument: sharp, memorable, devastating.

2) I mentioned the other week that I was rereading Aristotle’s The Politics (350 BC). This week, I thought a little about the part on citizenship. I like the short opening section (3.1) of this part, in which Aristotle sets about defining the term ‘citizen’, within wider discussion of what ‘the state’ is. Having ruled out the sufficiency of both “mere residence in a place” and having “access to legal processes”, on the grounds that both are open to “resident foreigners”, he turns to the relevance of political participation. Citizens, he argues, are people who participate by “giving judgment” and holding “unlimited” office, by which he means offices like juror and assembly member, which have no restrictions around length of tenure.

Now, the edition of The Politics I was reading features a useful footnote at this stage, reminding you that the ‘assembly’ that Aristotle is referring to here just happens to be made up of “all the citizens of a state”! Nevertheless, whether you seek to understand the state by considering who counts as its members, or whether you seek to understand the citizens by considering what bands them together, there’s an attractive freedom to this kind of functionalist approach. Its freedom is underlined in the following even shorter section (3.2), where Aristotle rules out the need for having citizen parents, to be a citizen. Rather, he tells us, if someone participates in the right way, then they are a citizen.

Of course, I haven’t mentioned how all this is tied up in Aristotelian context about different kinds of state. Or its link to Aristotle’s depressing belief that some humans are “natural slaves”. (Do read my friend Josh Ober on this topic.) All that said, I’m happy to hijack Aristotle’s approach to citizenship for a somewhat anachronistic purpose, and point out that focusing on the vast functional civic value of the citizen provides an oddly currently overlooked opportunity within the range of strong arguments in favour of liberal immigration policies.

3) The Prague Orgy (1985) is a novella by Philip Roth about an American novelist’s trip to Soviet Czechoslovakia. It’s funny and deep, as well as shocking in parts. But I just finished reading it, and want to think about it some more. For now, therefore, I’ll simply give you a few lines that particularly struck me:

“The workmen at their beer remind me of Bolotka, a janitor in a museum now that he no longer runs his theater. "This," Bolotka explains, "is the way we arrange things now. The menial work is done by the writers and the teachers and the construction engineers, and the construction is run by the drunks and the crooks. Half a million people have been fired from their jobs. Everything is run by the drunks and the crooks. They get along better with the Russians." I imagine Styron washing glasses in a Penn Station barroom, Susan Sontag wrapping buns at a Broadway bakery, Gore Vidal bicycling salamis to school lunchrooms in Queens — I look at the filthy floor and see myself sweeping it.”2

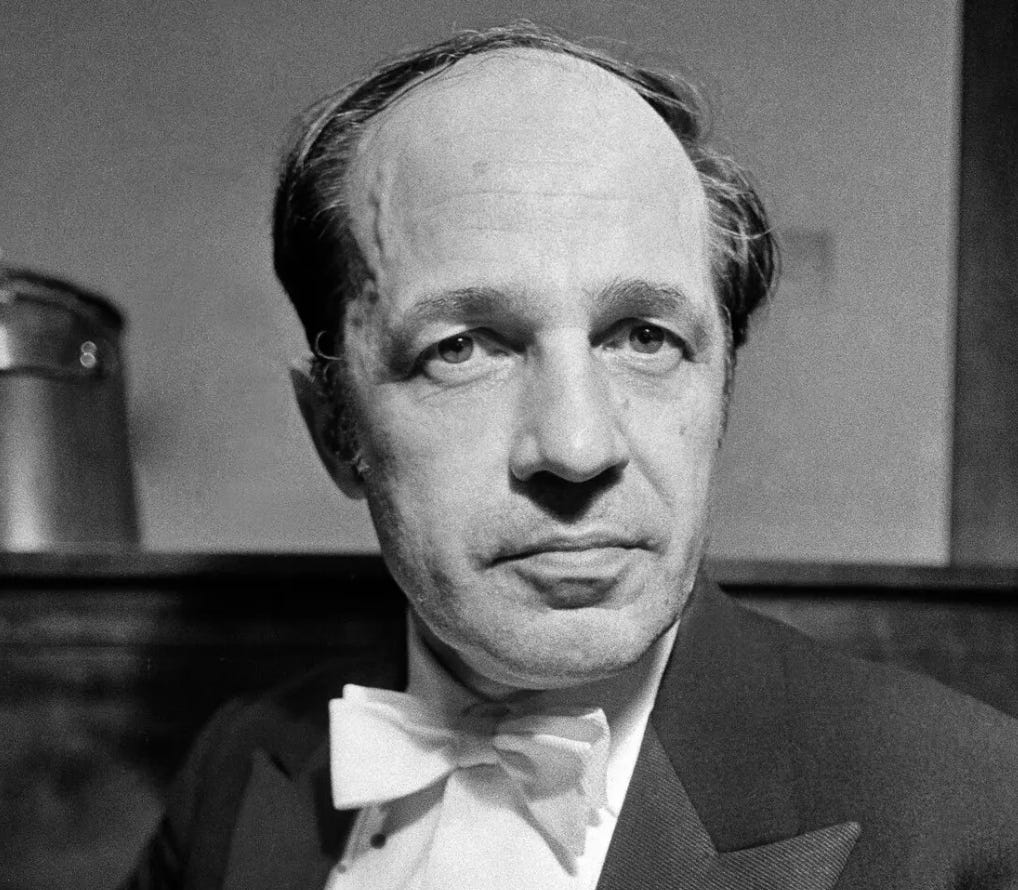

4) This recent New York Times piece celebrating the centenary of Pierre Boulez’s birth is worth reading whether you’re into modern composition or modern architecture. How long will these things count as modern, you ask?

5) I spent the weekend in Baltimore. As well as eating the best crab-cake sandwich, and taking the public water taxi past the excellent factories along the harbour front, I went to see Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962) at the Everyman Theatre. I already loved the play (although The Goat is surely the GOAT). But the actors, all members of the Everyman’s resident company, were also excellent. I can’t think of a UK theatre that comes close to the Everyman in representing the classic ‘repertory’ style.

p.276.

pp.60-61.