five top things i’ve been reading (fifty-second edition!)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

Abolishing Jury Trials Is a Direct Assault on English Liberty, Jack Salmon

Professional Foul, Tom Stoppard

Works of Love, Søren Kierkegaard

Why Is Ice Slippery? A New Hypothesis Slides Into the Chat, Paulina Rowińska

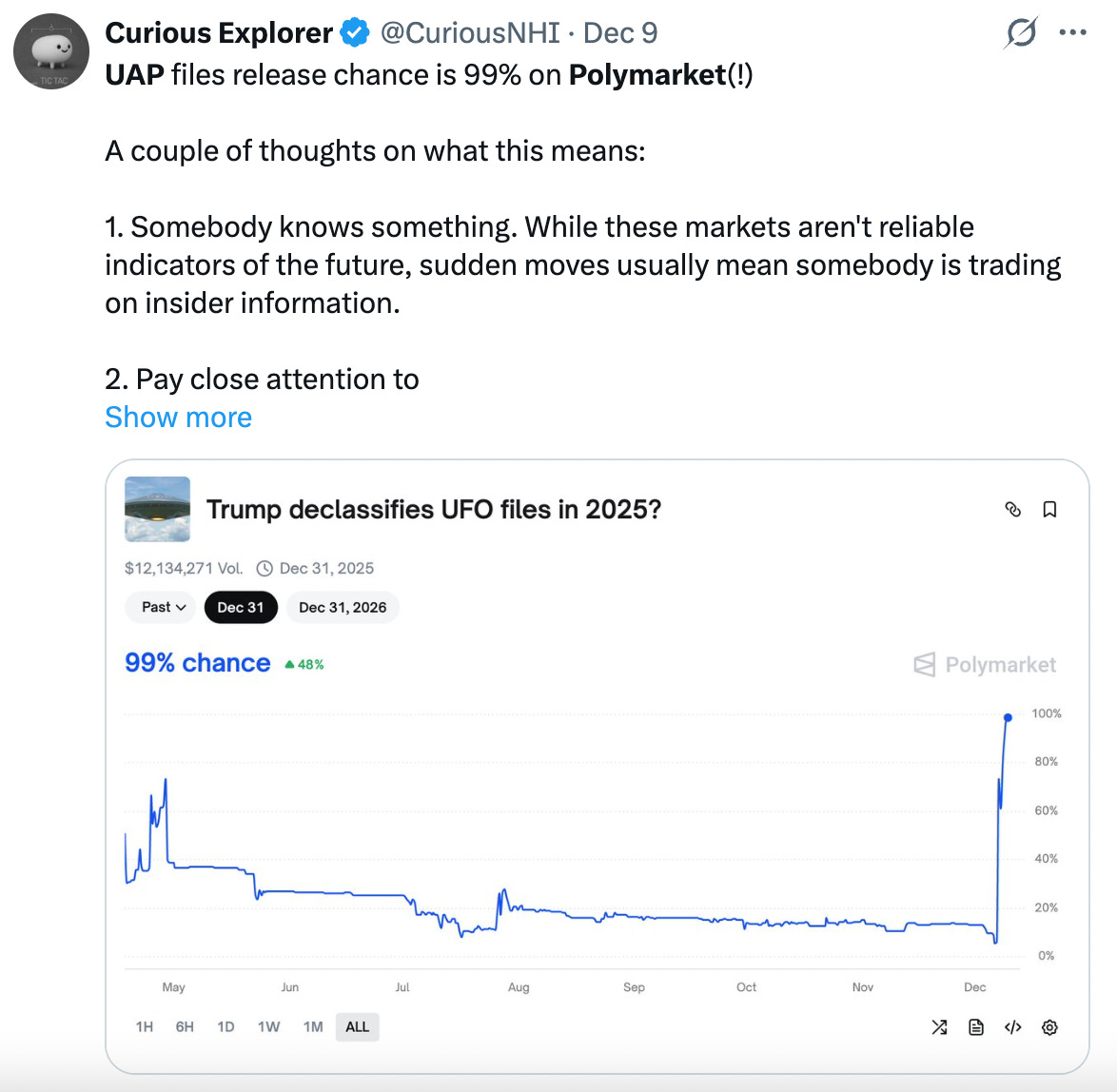

UAP Twitter

This is the fifty-second (!) in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) The UK government recently announced plans to reduce the use of juries in England and Wales. If these reforms go ahead, then criminal cases “with a likely sentence of three years or less [will be] heard by a Judge alone”, according to a government press release. From the start of this press release, it’s clear why the government has decided to pursue this controversial reform: the ever-growing backlog of court cases has taken the system to “the brink of total collapse”.

It’s hard to deny the seriousness of the court backlog problem. And being brought in as a sticking plaster against systemic collapse isn’t sufficient to make a reform a bad idea. I mean, yes, it’s better when reforms represent improvements in themselves. But sometimes sticking-plaster reforms can be justified — at least temporarily.

Preventing collapse isn’t sufficient to make a reform a good idea, either, however! Sure, if the NHS was about to collapse, then a reform that involved offering suicide drugs to the sick might well save the day. But that wouldn’t make it okay!

There are other reasons to doubt the value of this reform to the justice system beyond its knee-jerk nature, however. My friend and colleague Jack Salmon sets out many of these reasons in an article for The Unseen and The Unsaid. In particular, he rails against the illiberal “hollowing out” of the justice system for the sake of efficiency:

“When Magna Carta enshrined that no free man could be imprisoned ‘except by the lawful judgment of his peers,’ it crystallized the animating belief of English liberty: no ruler, no official, no judge may deprive a person of freedom unless the community concurs. A jury is not a procedural formality; it is the last and most enduring check on the abuse of state power. To sweep away this tradition because the courts are burdened, and the backlog large is to abandon the very idea that justice is more than administrative throughput.”

Jack is also emphasising the democratic nature of the jury system, therefore. And the risks involved in dismantling a system that has been built slowly and organically.

I’m less concerned with how the jury system came into being, to be honest. Tradition is a conditional good. But I strongly agree with Jack about the risks of depending on efficiency as the sole relevant value when making reforms to a justice system, and about the risks of fully outsourcing discrete elements of such a system to experts.

Involving the public in the determination of criminal wrongdoing provides checks on power at the level of the court case. But it’s also crucial to ensuring the transparency necessary to maintaining the system’s legitimacy, more generally.

The press release champions the government’s reforms as ‘swift’. But if the involvement of Jack’s “ordinary people” is bypassed in the haste of addressing current delays — as catastrophic as those delays are proving — then the UK will be another step forward on its sad march towards the domination of unaccountable centralised control.

2) This week, I read a load of things by and about Tom Stoppard, in preparation for the first episode of The Street Porter and The Philosopher. This is the podcast that Henry Oliver and I have launched as part of The Pursuit of Liberalism.

In this first episode, we focused on Stoppard as a liberal playwright. (Watch out for more episodes on liberalism in the arts!) My favourite of Stoppard’s plays is Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966). But one that I haven’t seen, and which I read for the first time this week, is Professional Foul (1978), much of which takes place at a philosophy conference in Prague.

As I mentioned in the episode, I found some of the philosophy in this play a bit disappointing. But I particularly enjoyed the part where a philosophy of language paper causes problems for the conference’s simultaneous translators:

STONE: John enters this competition and afterwards Mary says, ‘Well, you certainly ate well!’ Now Mary seems to be saying that John ate skilfully - with refinement. And again, I ask you to imagine a competition where the amount of food eaten is taken into account along with refinement of table manners. Now Mary says to John, ‘Well, you didn’t eat very well, but at least you ate well.’

INTERPRETER: Alors, vous n’avez pas bien mangé ... mais ...

(All INTERPRETERS baffled by this.)

Hilarious.1

3) I read some Kierkegaard last night. I like everything about the front cover of my copy of his Works of Love (2009). It looks fantastic, and the inclusion of a Wittgenstein puff quote makes me laugh. The section I read, however — Mercifulness, a Work of Love, Even if It Can Give Nothing and Is Capable of Doing Nothing — was quite frustrating.

The central point Kierkegaard makes in this essay is that you can be merciful even if you have no money. He makes some other related points, particularly: 1) that this central point gives us reason to focus on the goodness of mercifulness over the goodness of charity, so as to affirm that the poor can do good; and 2) more strongly, that “really to be able to be merciful is a far greater perfection than to have money and consequently to be able to give”.

Kierkegaard makes these points over and again, with varying degrees of clarity, often surrounded by over-claims in the form of unhelpful ‘only’s. “Preaching should be solely and only about mercifulness”, he demands with abandon, for instance.

He also tells us that “the world has understanding only for money”. In this context, he moves towards telling us that it’s not just that being merciful is better than being charitable, but that being charitable is not good. Here, he emphasises that money is bad in itself, and suggests that having money — even when this is to give to others in need — is always bad. Nonetheless, he retains throughout the essay the claim that because “the greatness of the gift increases in proportion to the greatness of the poverty“, therefore “one penny can become so important, become the most significant gift”.

It feels that not only does Kierkegaard contradict himself about the relevance of money, but that he corners himself into being able to assess the value of actions only in the context of money. Though, of course, some would say that this is him making a meta-comment on its all-pervasiveness!

Nonetheless, I do like the simple point he laboriously makes about the goodness of an action lying in more than its financial implications. And I also like his claim about it being impossible to depict mercy in a painting (though he then undermines this by saying that people can be depicted as “objects of mercy”!). But, as ever when I read this kind of philosophy, I want it all to be so much tighter.

If you’d like to read something really good on the topic of mercy, try this.

4) This evening, I enjoyed reading this Quanta Magazine article about ice, by Paulina Rowińska. Rowińska begins by explaining that the jury’s been out for a long time on why it is that ice is slippery, but that three standard answers to this question have recently been joined by a fourth.

The standard answers, according to Rowińska, centre on why it is that a melty “lubricating, liquidlike” layer forms on the surface of ice. The first answer tells us that this layer forms when pressure is exerted on ice. The second, that the layer forms when something slides against ice and causes friction. And the third, that the surface of ice is predisposed to this melty texture owing to its molecular patterns.

The fourth answer, Rowińska then reveals, retains the second answer’s focus on sliding, but denies the focus of all three on the meltiness of the top layer. Rather, advocates of the fourth answer believe that the key to understanding ice’s slipperiness might lie in a comparison with diamonds.

When diamonds slide against each other, it seems, “atoms on the surface [are] mechanically pulled out of their bonds, which allow[s] them to move, form new bonds, and so on”. This results in an “amorphous” layer, which “behaves more like a liquid than a solid”. So perhaps it’s not that ice is slippery because it becomes melty on top, but rather because it becomes amorphous!

I didn’t find Rowińska’s explanation of this new answer particularly clear, and I have some questions about the standard answers. But it’s such cool (sorry) stuff, that I’ll search out the scientists’ paper sometime soon.

5) If you’re not following UAP Twitter, you’re missing out..

Obviously this isn’t the main source of humour here, but I find these uses of ‘now’ amusing. The first now, particularly in the context of the second and Stoppard’s italicisation of it, feels like he’s making fun of philosophers for overusing the word in that way. I know I’m guilty of this..