five top things i’ve been reading (thirty-second edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

Robert Nozick’s Final Interview, Robert Nozick and Julian Sanchez

Political Liberalism, John Rawls

The Future of Liberalism, Peter J. Boettke

Lanzarote, Michel Houellebecq

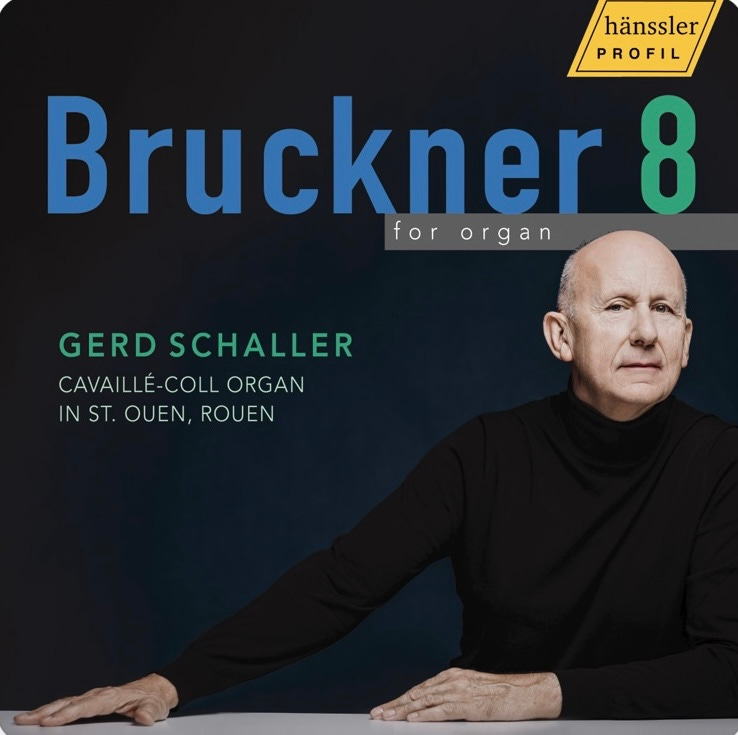

Bruckner 8 for organ, Gerd Schaller

This is the thirty-second in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) In this final interview (2001), Robert Nozick sets out his ideas on a wide range of philosophical problems, in response to pressing questions from Julian Sanchez. Some of these problems cohere specifically around the generative role Nozick affords to human evolution in his then-recent book Invariances. Particularly interesting, to that end, is what Nozick has to say on the nature and development of human consciousness, and on the possible variance of scientific laws.

But along the way, Nozick branches out into everything from hierarchies of importance in the ethical domain, to the incoherence of some popular theories advanced by Popper and Rand, to substantive differences between different notions of relativism. This interview is also the source of Nozick’s famous line: “the rumours of my deviation (or apostasy!) from libertarianism were much exaggerated”.

Two sections of the interview that I particularly enjoyed are broadly epistemological. The first of these sections involves Nozick talking about the relation between knowing “what’s the right thing” and being obligated to do it. The second focuses on the relation between knowing about science and doing good metaphysics. One reason I enjoyed both of these sections was that they made me think of some works by my great friend John Heil.

One of my favourite philosophy papers is Heil’s Believing Reasonably (1992). In this paper, among other things, Heil discusses the question of doxastic voluntarism — that is, whether we have “direct voluntary control” over our belief formation. Here, he argues that “[e]ven if believing is not something one can sensibly set out to do directly, one is often in a position to take steps that will, predictably, result in the formation (or extinction) of beliefs”. For instance, if you’re busy thinking about whether it’s true that some politician is correct on some issue, then you could make sure only to read reportage that aligns with that view.

I’ll write here about Heil’s paper at more length, sometime soon. But if you read the Nozick interview and want to think more about Nozick’s answer to his self-posed question “why should I believe the truth?”, then I recommend you read Believing Reasonably. Similarly, if you want to think more about how metaphysics trades on scientific truth, then read the opening section of Heil’s 2012 book The Universe as We Find it — which I wrote about in my ‘five top things I read in 2024’ piece.

Finally, I enjoyed what Nozick had to say about the importance of “meeting” rather than “dismissing” other people’s arguments. First, he makes an implicit point about the importance of focusing on the quality of an argument. Then, he says that when philosophy lecturers “dismiss arguments by scorn or contempt, so that the class doesn’t think about those arguments, and isn’t tempted to accept them”, then “[t]hose professors probably don’t know how to answer the arguments anyway”.

This reminds me that I also recently enjoyed reading this short blog post, by Elizabeth Barnes, on the personal value of disagreement.

2) I’m going to be a predictable political philosopher today, and go from Nozick to Rawls. Last week, while I was writing the piece I published here on the topic of ‘what is liberalism?’, I thought hard about the section of Rawls’ second book, Political Liberalism (1993), in which he defines his influential term ‘comprehensive doctrine’.

Like many Rawls Terms, ‘comprehensive doctrine’ has become both widely employed and widely inaccurately employed. This isn’t to deny the value in redefining terms. It’s just to point out there’s a difference between trying to employ a Rawls Term in the way Rawls did, and arguing that Rawls should’ve employed his terms differently. Anyway, as I discuss in my liberalism piece,

“A comprehensive doctrine, on Rawls’ account, is a moral doctrine that’s both general and comprehensive. Rawls gives utilitarianism as an example of this kind of doctrine. Utilitarianism is ‘general’, because its principled direction applies to a wide range of societal focuses, from individual conduct to institutional organisation and beyond. And it’s ‘comprehensive’ because it provides similarly wide-ranging conceptions of value and virtue: informing all kinds of personal and interpersonal conduct.”

3) Since having published my liberalism piece last week, various kind people have sent me links to other recent pieces of writing on liberalism. One of these, which I particularly enjoyed, is The Future of Liberalism, by my excellent Mercatus colleague Pete Boettke. It’s a call to arms, arguing, ultimately, that liberalism has a bright future. Indeed, that it must have — that we need it!

Cohering around a Kantian double aim of furthering cosmopolitanism and peace, Boettke’s liberalism is both aspirational and realist; he concludes that creative liberal solutions can be found to even the most intractable-seeming societal problems. I particularly liked his defence of liberalism in the face of critics who are “fundamentally confus[ed]” about it.

I also really enjoyed my friend Henry Oliver’s recent take on classical liberalism. It’s a great piece of writing. I don’t agree with Oliver that liberalism “must have a sense of history” — for me, that would make liberalism too contingent. But I'm happy to conceive of classical liberalism as a particular liberal trend across time, and, to that extent, as contingent on particular historical facts. Anyway, do go read his piece!

4) On Saturday, I reread Michel Houellebecq's Lanzarote (2000). It's a short novel about a pessimistic French guy who goes on holiday. It’s quite like Houellebecq’s slightly later longer novel Platform (2001), therefore, but less developed. Platform, which I also reread this weekend, is most notable for a reason I can't mention, in case you haven’t already read it. Except to say that I’ve suddenly realised its extreme overlap with an English novel published about a decade later…1

Lanzarote, regardless of its brevity, does a decent job of representing Houellebecq. He's a fantastic writer who manages to make overlapping stories, with extremely overlapping everyman main characters, totally compelling.2 A core function of these main characters is, on my view, to remind us of the astonishing genre that is fiction. Sure, these main characters hold views that overlap with Houellebecq's own, if his non-fiction is to be taken at face value. But novels' face value is fictional value. You don't like the main character's misogynistic throwaways? You don't like his extreme behaviours, even more? And as for his politics? These things are indirect comments, at most! But fiction, all through.

5) From the opening wall of sound onwards, I loved this new recording of Gerd Schaller playing his organ transcription of Bruckner 8. Generally, I’m not really into the Bruckner symphonies — partly as a result of Bruckner-motet-overkill back when I used to sing, and partly, it would seem, because I’ve been listening to the wrong instruments playing them.

A prize (in the form of a shoutout next week) to the first person to work out which English novel I’m referring to. o3 failed miserably!

Ok, they’re a very particular kind of everyman..

Thanks! Excited to read the Boettke paper!