five top things i’ve been reading (fifty-fifth edition)

the latest in a regular ‘top 5’ series

The Unreality of Time, J.M.E. McTaggart

Time Without Change, Sydney Shoemaker

Minor Black Figures, Brandon Taylor

Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman

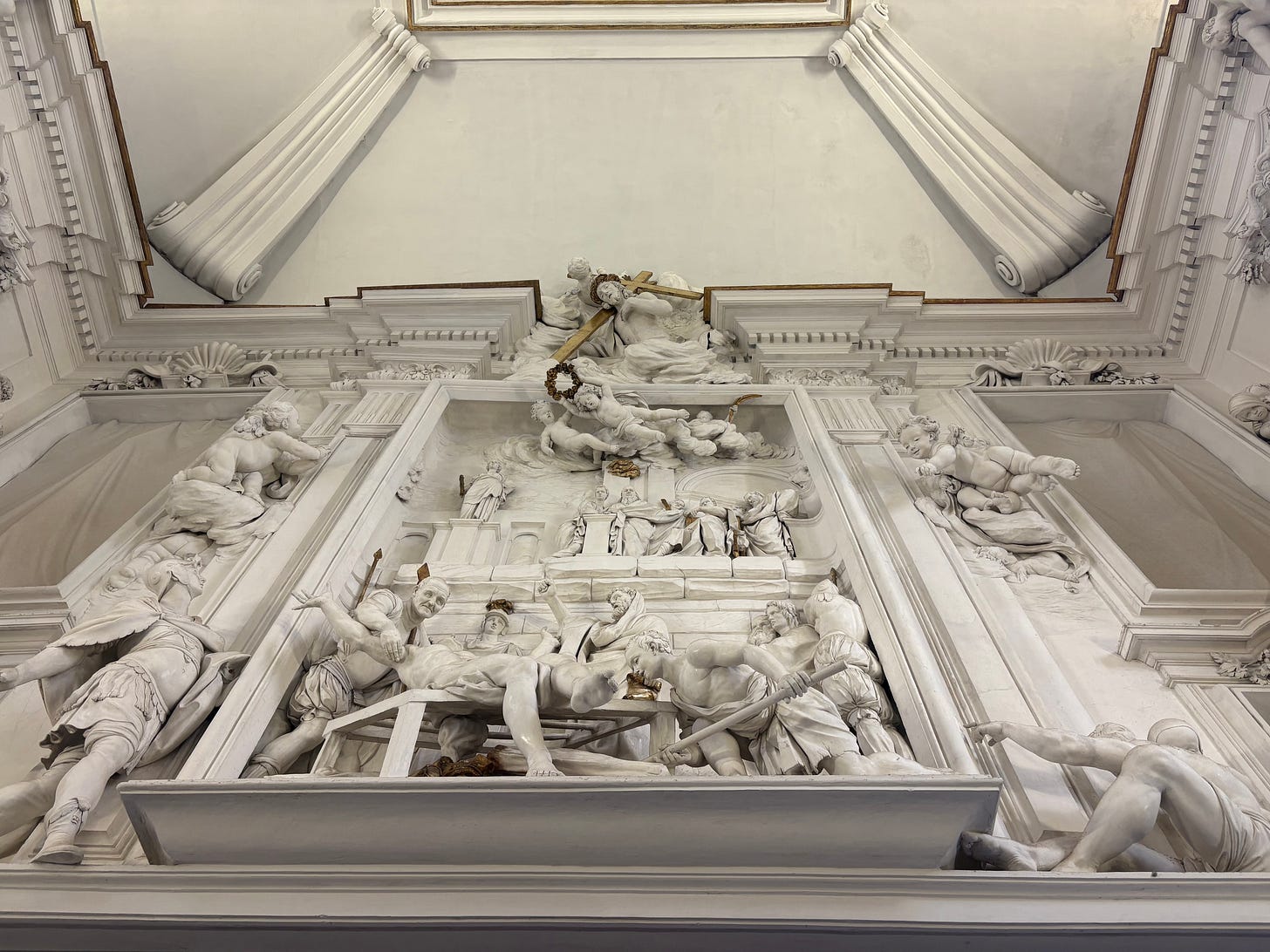

Serpotta’s stucco

This is the fifty-fifth in a weekly series. It’s a little later than usual, owing to travel, illness, and various other factors. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) On Tuesday, I published a piece about how Solvej Balle interacts with the philosophy of time in her On the Calculation of Volume novels. While writing my Balle piece, I reread two of my favourite philosophy of time papers, both classics. The first of these is J.M.E. McTaggart’s The Unreality of Time (1908). As I discussed in my Balle piece, it’s in this paper that McTaggart introduces his influential ‘A series and B series’ framing:

“These two series offer us different ways of thinking about when events happen. McTaggart picks holes in both series, but many philosophers identify as either A or B! If you’re an A series person, then you think of events as happening in the past, or the present, or the future. Whereas, if you’re a B series person, you think of events as happening in relation to one another — in the sense, for instance, that some particular event happened “earlier than” some other event, but “later than” another one.

One thing to note about this second view, therefore, is that these “earlier than” and “later than” kinds of relations always hold. That is, no matter what else is going on, and no matter what time it is, Julius Caesar was always killed earlier than Franz Ferdinand was killed. Events on the B series have a fixedness, therefore. Whereas, when you think about events in the context of the A series, they have a non-fixedness. That is, the killing of Julius Caesar switched from being in the future to being in the present, and it also switched from being in the present to being in the past.”

This distinction serves largely as a means to an end for McTaggart in this paper, however — although it’s clearly a useful and interesting distinction, in itself.

Rather, McTaggart’s main aim here is to persuade us that time is not real. He uses the A series, in particular, to help him in this. Indeed, the central argument of this paper hinges on the following two A-series-claims being true: 1) that time depends on the A series; and 2) that the A series cannot exist in reality. McTaggart pretty much asserts the first of these claims from near the beginning of the paper, although he does then attempt to back this up. He also spends valuable time making it clear that the A series is an ordered series — that is, that its events can only shift ‘stages’ in one direction, from future to past.

The really crucial part of the paper, however, is where McTaggart tries to persuade us about the second A-series-claim: that the A series cannot exist in reality. His core argument here depends on the idea that “the characteristics of the A series are mutually incompatible and yet all true of every term”, and that this means that the A series cannot be “applied to reality” without a contradiction arising.

A contradiction arises, McTaggart tells us, because whether we take the elements of the A series to be relations or qualities, a single event cannot take place in the future, in the past, and in the present, unless we assume that time exists. This is because, as McTaggart sees it, all events have to be able to be in all three stages (questionable, but okay!), yet this cannot be the case without either each event being in all three simultaneously (self-defeating!), or without presupposing the existence of time (bad!), so we become stuck in a vicious circle.

McTaggart addresses some obvious objections to this conclusion, not least the objection that perhaps time is “ultimate”. Perhaps that is, time is the kind of thing — like truth and goodness, he analogises — that cannot be explained without reference to itself. In other words, perhaps time is the kind of thing that does not ‘reduce’. Well, to conclude this would be to make a false equivalence, McTaggart parries, because it’s not that the A series “does not admit of a valid explanation”, but rather that it cannot be “applied to reality” without a contradiction! Now, I think it’s quite unhelpful that he keeps focusing on the contradiction, rather than the vicious circle, which is where the real pressure lies. But this point about the difference between being explicable and being able to exist is another useful and interesting offering from McTaggart.

My favourite thing about this paper, however, is the introduction of the C series (!) The C series is a non-temporal ordering of events. What I mean by this is that the events that form the elements of a C series are in a set order, but that time plays no role either in the elements’ placing within the order, or in the directionality of the order. Here, McTaggart gives us the lovely (aptly letter-based!) analogy of the alphabet.

He goes on to use the C series within various arguments before telling us, almost offhand and at the very end of the paper, that while he has concluded that the A series (and also the B series, which I haven’t had time to get into here) do not “really exist”, he thinks it’s “probable” that the C series does. He offers a few quick glimpses of what such a thing might mean, before leaving us totally hanging. Here, he throws us the fantastic line that “on the solution of these questions it may be that our hopes and fears for the universe depend for their confirmation or rejection”!

2) The other classic philosophy of time paper I reread this week is Time Without Change by Sydney Shoemaker (1969). This is a paper about the relation between time and change. As I discussed in my Balle piece, there’s a big philosophical debate about this relation, in which the two main positions are called substantivalism and relationism:

“First, some people think that time is independent from change. On this view, time can be thought of as a container. That is, people who hold this view tell us that even if events stopped unfolding — if, instead, somehow everything in the world ‘froze’ — then time would nonetheless continue. The container wouldn’t go away! It could have frozen contents, and it could have no contents, and it would nonetheless persist. This view is called substantivalism, because its proponents typically think of time as a substance. Isaac Newton was one of them.

Some other people think, however, that there cannot be time without change. On this second view, if the kind of ‘freeze’ took place that meant events stopped unfolding, then time would also be frozen.⁸ This view is called relationism, because on this view, time is reduced to relations between events, or between things and events. So on this view, there is no container. There are just the things that, on the container view, are the container’s contents! Leibniz held this view.”1

Shoemaker’s main aim in this paper is to persuade us that “changeless intervals” are conceivable. In other words, to persuade us that it’s reasonable to believe that such things are logically possible (as opposed to physically possible under our actual laws of physics!). Of course, if Shoemaker is right about the possibility of changeless intervals, then this has big implications for relationism, which he presents as the standard view. Here, he refers to David Hume’s claim that “’tis impossible to conceive ... a time when there was no succession or change in any real existence”.

In this context, Shoemaker sets about creating a wonderful world of ‘local freezes’. That is, he gets us to imagine a universe in which events could stop unfolding in certain discrete areas, while time ‘ticked on’ elsewhere. He describes what goes on “during” (!) these local freezes quite beautifully, telling us that:

“it is impossible for people from other regions to pass into the region where the freeze exists, but when inhabitants of other regions enter it immediately following the end of a freeze they find that everything is as it would have been if the period of the freeze had not occurred. Eggs laid just prior to the beginning of a freeze lasting a year are found to be perfectly fresh; a glass of beer drawn just prior to the beginning of the freeze still has its head of foam, and so forth. And this remains so even when they make the finest measurements, and the most sophisticated tests, available to them; even radioactive decay, if such exists in this world, is found to be completely arrested during the period of a local freeze.”

The main argument that Shoemaker advances in this paper depends, however, on a whole load of further ‘truths’ about these local freezes — details, that is, about their regularity, their duration, and even the “sluggish” behaviour by which we can identify their soon-to-be-frozen inhabitants! Shoemaker tells us that if we knew about all these things, then we could work out when a ‘general freeze’ would take place. And a general freeze would be a freeze in which, unlike the local freezes, time would not continue to ‘tick on’ anywhere!

Shoemaker addresses various objections against using his local-to-general-freeze argument to cut away at the prevalence of relationism. He also tells us important and interesting things about ‘McTaggartian changes’ (or ‘Cambridge changes’, as these kinds of changes later, broadly, became known.) Now, I love all of this stuff, and I don’t buy relationism, and there are few papers I enjoy reading more than this one. But I’m afraid I find its central substance simply too much like science fiction to be philosophically convincing.

3) I started reading Brandon Taylor’s Minor Black Figures (2025) a couple of months ago, but I struggled to get past the first chapter. It all just seemed so much more ‘on the nose’ than Taylor’s previous two novels, which I’d really loved. The Late Americans, in particular, I was fully convinced was one of the best novels of the past decade. Yet this new novel felt so self-conscious! It felt as if Taylor was trying really hard to write a Great Novel about Art.

I’m extremely glad that I came back to it and persisted, however, because by a third of the way through, I came to believe that Taylor had indeed written a Great Novel — even if it was a Great Novel about a romantic relationship, rather than a Great Novel about Art. By the end, however, I came to accept that it was indeed, at least in parts, a Great Novel about Art.

Okay, I stand by my view on its opening chapter. And I also stand by my view that Taylor’s greatest strength, in this novel and elsewhere, is writing about romantic relationships. Many kinds of relationships, actually! It helps here that he’s astonishingly good at writing conversations. I’m not sure I can think of anyone better at this — anyone who’s writing today, anyway. But this new novel also shows how great Taylor is at writing about the city, something that wasn’t so clear from the previous novels, which were largely (beautifully!) set in the country and in the town.

I’m afraid I feel compelled to finish by saying that I found the explicitly ‘political’ moments of this new novel jarring and cliched: the occasional worthy monologues on topics like consumerism and homelessness. But the implicit stuff — including stuff on both of those topics — is really wonderful. And the art that ‘happens’ in Minor Black Figures is fully convincing. At its best, this is the best new novel I’ve read in decades.

4) Last spring, I wrote about Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (1855). Every time I come back to this collection, which is often these days, I’m taken away by its sense of modernity. This week, Whitman’s use of a “subtle electric fire” as a metaphor for love made me look up when electric fires were invented!2

5) I wrote most of this post on a flight from Palermo, where I saw many great things this week. I won’t easily forget the shocking brightness of Serpotta’s stucco at the Oratorio di San Lorenzo.

Thanks to GPT for the amusing pictures of McTaggart and Shoemaker.

As I footnoted in my Balle piece: “There are many complex versions of each of these theories! Here, I’ve just produced a simple version of each, so that people who don’t know anything about this great philosophical debate can get into it a little, while I have fun expounding on Balle Time.”

You can find this metaphor in Oh You Whom I Often And Silently Come.

“… and I don’t buy relationism….”

Now if that’s not a delicious tidbit… I didn’t read the whole Balle piece because you convinced me I should read the books. Is there somewhere you summarize your skepticism about relationism (without spoilers)?

As a theatre major who, in high school, read a lot of Isaac Asimov essays about astrophysics, I just came up with a thought about time, after reading this great newsletter. Maybe time is an emergent property of the universe, of entropy, of change. It's not a thing in itself but a way to measure change. Okay, back to memorizing my lines for that production of Fiddler on the Roof I'm going to be in.

PS, like Scrith, I stopped reading your Balle piece because I decided i should read those books first. Obvisously, Balle needs you on her marketing team.