five top things i've been reading (twelfth edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

TLDR:

The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell

Knowing How and Knowing That, Gilbert Ryle

Jailed, Failed, Forgotten, Dani Garavelli

Poems and Antipoems, Nicanor Parra

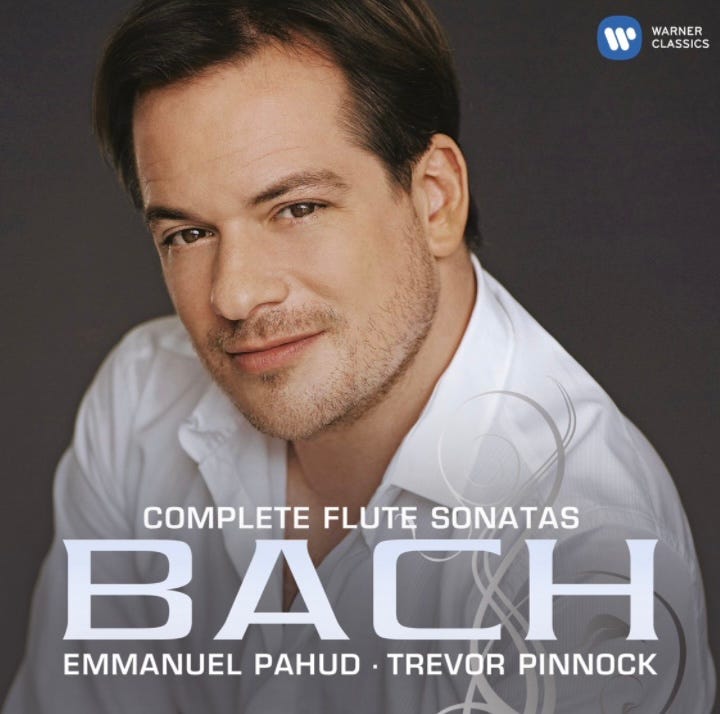

Bach Flute Sonata in E Minor, Emmanuel Pahud and Trevor Pinnock

This is the twelfth in a regular Sunday series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) In The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), George Orwell attempts to argue in favour of socialism by describing the hardships of poverty and unemployment. If only, he tells us, socialists could persuade the struggling bank clerk to identify with the out-of-work miner. And if only, he tells us, socialists could get past their image problem (priggish vegetarians!) and their association with industrialisation (the machines will take our jobs and dull our minds!). Then we’d all live happily ever after. Or, minimally, we’d beat the fascists in the fight for Europe.

It’s an important book. Particularly powerful is Orwell’s chronicling of how unthinkably horrific the conditions were, for many people in England, less than a century ago. The section about ‘travelling’ in the mines – the miles-long horizontal journey, which the miners had to take bent-over to reach the coal seam, after their better-known vertical journey down hundreds of feet in a cage that sometimes smashed into the ground — was revelatory to me, even though I grew up in the North East, learning about mining at school and from my grandmother who spent her childhood in a pit village. I suspect most people from Wigan would have a similar reaction to Orwell’s depiction of 1930s life in the fixed caravans there. “One, for instance, measuring fourteen feet long, had seven people in it,” he reports. “Seven people in about 450 cubic feet of space; which is to say that each person had for his entire dwelling a space a good deal smaller than one compartment of a public lavatory.” The details go on and on. Details about boarding-house bed arrangements and fingerprints on bread at breakfast. Details about the lack of back doors on back-to-back housing. Details about the “palliative” solace of the unhealthy working-class diet. Details involving comparisons with the invader evils of the colonial criminal-justice system. Details of all the horrors we’re used to Orwell exposing.

Where Orwell fails, however, is in using these details to cash out his theory of socialism. Often, he falls back on the idea that socialists should champion justice and liberty, rather than economic policy. I think he’s right to emphasise this. The socialist cause, which has its ancient roots in ethical ideals, has surely been set back by its entanglement with Marxist economic thought. But if what Orwell wants is satisfactory living standards, then he needs to tell us how socialism will enable necessary productivity. And if what he wants is to “see to it that everyone does his fair share of the work and gets his fair share of the provisions”, then he has to undertake the hard work of arguing what a “fair share of the provisions” is, and advocate a feasible economic model that allocates along those lines whilst also maintaining those satisfactory living conditions.

I always learn a lot from Orwell. But if I want to read a values-focused socialist telling me about socialism, then I’ll stick with G.A. Cohen. In If You’re an Egalitarian, How Come You’re So Rich, Cohen explains why he dropped his Marxist commitments. And in Why Not Socialism?, Cohen admits his concerns about socialism’s feasibility problems. We’d do well to listen to Orwell about the importance of work. We should definitely listen to him about the importance of forming broad coalitions against authoritarian politicians. But if you’re looking for arguments in favour of socialism, then Wigan Pier isn’t the place.

2) As you might expect from its title, Gilbert Ryle’s Knowing How and Knowing That (1945) is focused on knowledge-how, knowledge-that, and their relation. There’s a “prevailing doctrine”, Ryle begins, which depends on a separation between “acts of thinking” and practical activity. This doctrine pushes the idea that “doing things is never itself an exercise of intelligence, but is, at best, a process introduced and somehow steered by some ulterior act of theorising”. In other words, you can’t intelligently ride the bike. But you use your intelligence about bike-riding to avoid falling off!

Ryle argues against the prevailing doctrine. He argues that the relation it describes between acts of thinking and practical activity is incoherent (what kind of “Janus-headed go-between faculty” could enable your bike-riding to be intelligence-steered, if there is no intelligent action?). He argues that it’s wrong to try to define knowledge-how in terms of knowledge-that (education is about the “inculcation” of skills, not the “imparting” of information!). And he argues that, really, the arrow flies the other way (you don’t know the distance between two places, if you can’t use the information you’ve learned about their distance in an intelligent way!).

It’s a compelling and enjoyable article. It probably doesn’t need so many reiterative flourishes (“Rules, like birds, must live before they can be stuffed”!), though they definitely add colour. And whilst Ryle strikes many blows against the prevailing doctrine, it sometimes feels like he’s trying to persuade us that knowledge-that is never relevant to knowledge-how. I’m happy to accept, in at least some cases, that the latter “cannot be built up by accumulating pieces of” the former. But this doesn’t depend on Ryle convincing me that philosophy “cannot be imparted but only inculcated”.

3) Dani Garavelli’s recent LRB article, Jailed, Failed, Forgotten, exemplifies the journalistic exposure of injustice. Focused on recent teenage suicides in Scottish custody, Garavelli manages to communicate both individual tragedy and institutional failing. The Scottish rate of such suicides, she argues, is particularly concerning, when tracked against the rates of comparable nations, including England and Wales.1 But she never loses sight of the way in which every teenage suicide is a world-ending catastrophe, and every teenage custodial suicide is an intolerable state failure.

One underlying theme of Garavelli’s article is the way in which narratives about Scottish moral superiority prop up institutional corruption. Another is differential media interest in the deaths of these teenage prisoners, dependent on their class backgrounds and the seeming deservedness of their sentences. The real strength of the article, however, lies in Garavelli’s dogged pursuit of the detailed truths of each case. These are truths pertaining not only to how each teenager managed to kill themself while in custody, but also to who specifically failed them. It feels jarring to read the names of the staff involved; it’s hard to deny it’s justified.

4) Having enjoyed Neruda a few weeks ago, this week I read his compatriot Nicanor Parra’s classic collection Poems and Antipoems. Neruda easily retains his position as my favourite Chilean poet, but I keep thinking about Parra’s line “I am going to change the name of some things”.

5) This week, as most weeks, I listened several times to Emmanuel Pahud playing the third movement of Bach’s e minor flute sonata. The first movement of this sonata is probably more beautiful. But I particularly love the moment we first hear the flute in this third movement — and the moment its opening theme comes back at the recapitulation.

I wish she’d argued this point more clearly.