five top things i’ve been reading (fifty-sixth edition)

the latest in a regular ‘top 5’ series

Why Does Inequality Matter?, T.M. Scanlon

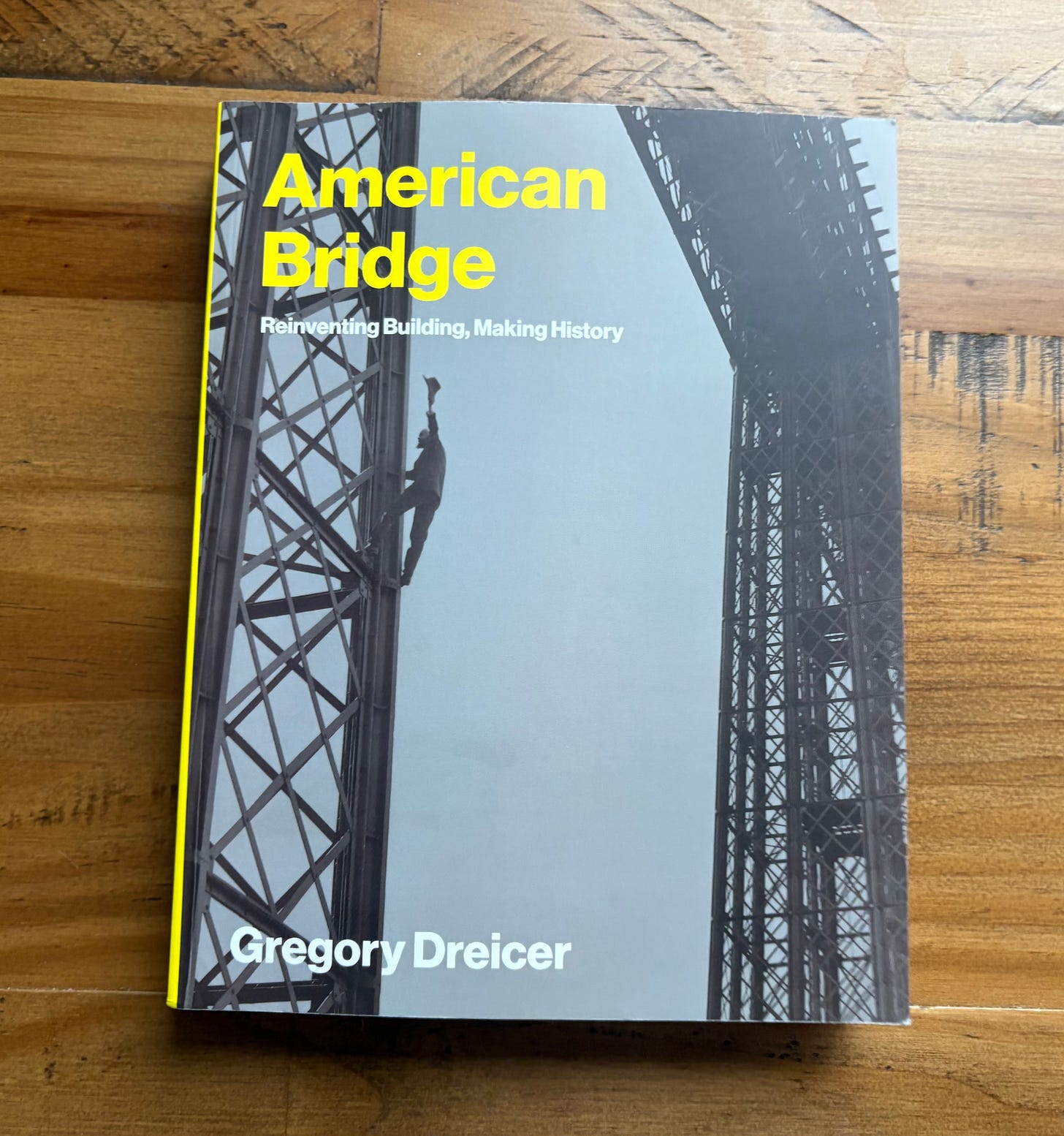

American Bridge, Gregory Dreicer

Second Acts and Semiquincentennials, Eileen Norcross

Why aren’t we using AI to advance justice? Amal Clooney and Philippa Webb

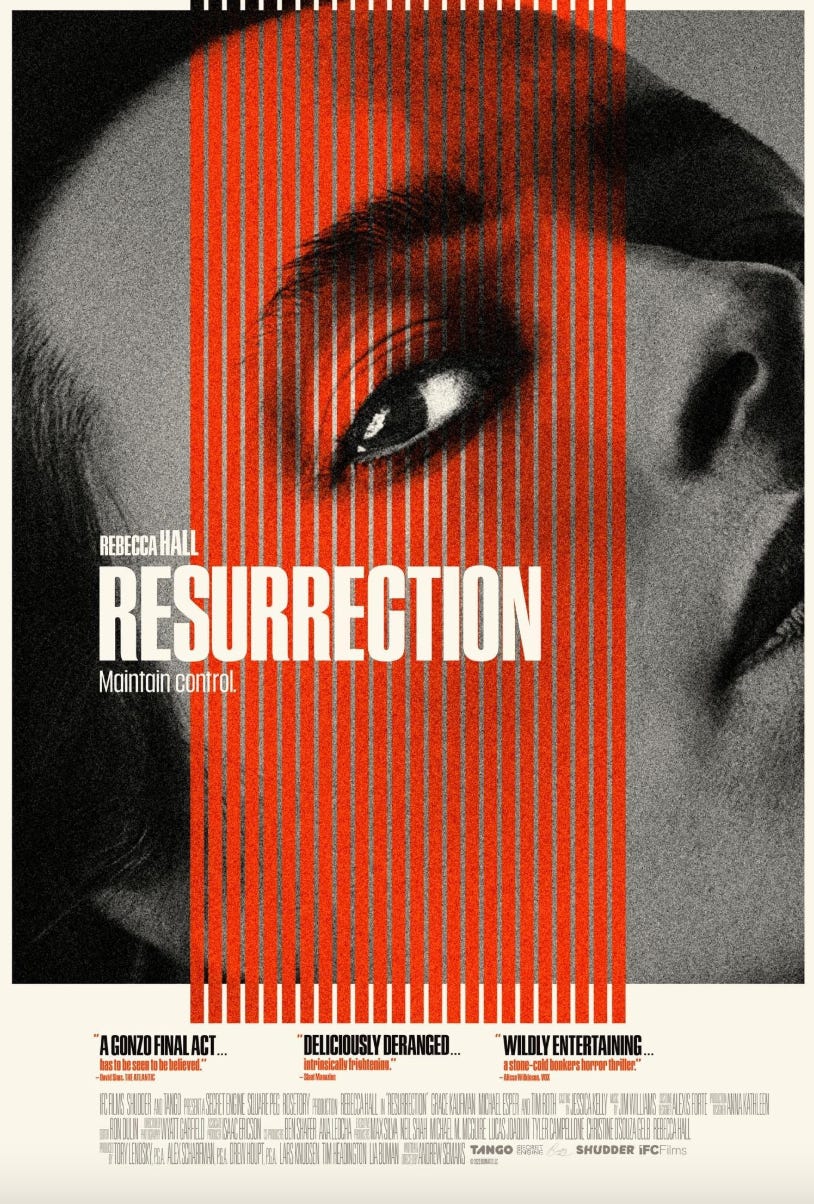

Resurrection, Bi Gan

This is the fifty-sixth in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) On Friday, I read some of Tim Scanlon’s Why Does Inequality Matter? (2018). I always enjoy reading Scanlon, not least because he’s such a clear writer. But I was reading this particular Scanlon book because I’m currently writing a piece entitled ‘what is equality?’, ahead of recording an episode of my Working Definition podcast in which my friend Teresa Bejan and I will address this question.

While I’m working out what I think about a particular philosophical topic, I tend to avoid reading other philosophers’ related writing. As I’ve written about here before — albeit in relation to my practices around using AI — working these things out for myself matters a great deal to me. But I’ve already thought and written and read lots about equality, and Scanlon makes some useful distinctions I want to discuss in my piece.

That said, for the most part, this book is quite light on the things I’m most interested in. In particular, Scanlon says near the start that:

“One important idea of equality that I will presuppose but not argue for is what might be called basic moral equality—the idea that everyone counts morally, regardless of differences such as their race, their gender, and where they live”.

I’ll probably refer to this statement in my piece, since I’m planning to argue that any serious inquiry into equality (or inequality or egalitarianism!) requires a proper account of what Scanlon gestures at as ‘basic moral equality’. This is because, on my liberal kind of approach anyway, such a thing bears extremely heavily on most moral questions, never mind most moral questions about the varying distributional matters that philosophers tend to group under concerns of equality.

Now, I’m not suggesting that Scanlon ignores basic moral equality in this book — and indeed, I didn’t read all of it! But I strongly believe that simply presupposing such a thing is almost always costly when it comes to making other equality-focused arguments.

I also wasn’t convinced by a crucial argument Scanlon makes, early on, to defend his focus in this book on six specific objections to inequality. These objections are the following: that inequality leads to (1) humiliating status differences, (2) unacceptable kinds of power use, (3) damage to economic opportunity, and (4) unfair influence on political institutions. And that inequality stems from (5) the violation of the principle of ‘equal concern’, and (6) unfairnesses within economic institutions. The argument that didn’t convince me about the joint significance of this particular set of objections can be found in the following extract:

“There may be other reasons for favoring equality, or for objecting to inequality, that I have not listed. I will focus on the objections I have listed because they seem to me important, but especially because there are interesting normative questions about the values that underlie them. Not all objections to inequality raise such questions. For example, as I mentioned earlier, inequality may be objectionable because it causes ill-health. It might also be argued that greater equality is desirable because inequality leads to social instability, or because equality contributes to economic efficiency by fostering a greater sense of solidarity and willingness to work hard for the common good. If the empirical assumptions underlying such claims are correct, then these are good reasons for regarding inequality as a bad thing. I am not discussing these reasons, however, because there seems to me nothing puzzling about the values that they appeal to. There is no question, for example, about whether ill health is bad. So the questions of whether these objections apply are purely empirical.”

But on this reasoning, then aren’t most — if not all — of Scanlon’s six objections also “good reasons for regarding inequality as a bad thing”? Isn’t there also “no question” about whether humiliation and unfairness are bad? Aren’t there questions about what kinds of “social instability” are justifiable? And about what kinds of ways of “fostering a greater sense of solidarity” are morally concerning? Now, I’m sure Scanlon goes on to make much stronger arguments about these matters elsewhere in the book, but I didn’t just buy this reasoning at all.

2) Gregory Dreicer’s American Bridge (2026) has a beautiful front cover. Indeed, if front covers are what count, then it might be the most beautiful book I own. There are also some great pictures — photos, diagrams, posters, more — inside this book. And on the rare occasions that Dreicer drags himself away from over-theorising and on to the technical bridge stuff, it’s a pretty good read.

Mostly, however, this is a book of over-claims, padding, grating metaphors (such-and-such “may allow us to change the story and build new bridges to the future” etc etc), and confused attempts at philosophical inquiry. There’s a particularly tortured bit where Dreicer sort of tries to distinguish lattices from tubes — which, to be fair, is at least one of the bits about bridges per se.

As it happens, I have sympathy for Dreicer’s biggest non-bridge point: that expanding evolutionary theory to try to explain societal development risks undercutting the relevance of human agency.1 But his argumentation skills aren’t strong enough to make this point compellingly, and it gets lost amongst all the other moaning — plus, I really really just wanted to read about bridges! Again, however, the pictures are great.

3) This week, I enjoyed reading Second Acts and Semiquincentennials — a new Substack piece by my friend and Mercatus colleague, Eileen Norcross. It’s a tightly written tribute to her aunt and uncle, who turned together towards travel in the latter half of their lives:

“My uncle launched his second act first. After two decades as an FBI Agent and upon his retirement from the Navy (captain), he started his own company as private investigator and security consultant.

[…]

My aunt loved to travel.

My uncle loved to fly planes, and to fly on them.

When the time was right they combined these interests. At a desk in the guest room my aunt followed suit starting her second act as a travel agent.”

I particularly like how Eileen shows us ways in which individualism and the common good are inherently bound up. How, for instance, the extensive realisation of a person's valuable talents and interests typically depends on cultural conditions and community support, as well as individual drive and commitment. And how the realisation of those kinds of talents and interests is good not only for individuals, but also — indeed as part of that! — for the groups of which they are members, including romantic partnerships.

I also enjoyed the bits about penguins.

4) This week, I also valued reading this Time piece, co-authored by my friend Pip Webb — a leading expert in international law — about the unrealised value of using AI to provide much-needed legal aid, across the world. Early on, a World Justice Project statistic is cited, telling us that “only about 10% of people reach a lawyer when they need one”.

Throughout, Pip discusses the work she’s been doing at Oxford, in collaboration with various organisations, to develop AI legal assistants and advisors. She explains how these tools can offer interactive multi-language support to people lacking access to necessary legal information and representation — including help for journalists under threat, and services to increase the efficiency and knowledge of lawyers and judges.

The piece begins with the following example:

“In Malawi, one in three women is a victim of violence. Almost one in ten girls is forced into marriage before turning 15. But fewer than 800 lawyers serve the population of 22 million. What chance does a girl in a rural village have of finding legal help—let alone affording it?”

I’m fully convinced that AI ventures like Pip’s will change the world.

5) A few days ago, I went to see Resurrection. I don’t know enough about Chinese cinema to know how revolutionary this film is. And my aphantasia puts me at a serious disadvantage when watching anything in which you’re supposed to realise that multiple characters are being played by the same actor (here multiply!).

It was all totally visually compelling, however — particularly the red-tinted 1999 section, which was my favourite section generally, although I think each of the five main sections works well individually, and in combination. If I had to guess what the whole thing is supposed to be ‘about’, then I suppose I’d go for either the distinction between need and obsession, or a Chinese political commitment to long-term cultural dominance.

But perhaps it’s just about a couple of guys fighting over a box.

I think this kind of expansionism also risks distracting us from the specific value of evolutionary theory to explaining species development, but I’m not sure that Dreicer would agree with me here, because he seems pretty down on Darwin.

"Thank you for citing our analysis, Rebecca! We also believe that AI has a huge potential to close the justice gap. We’re working to move the needle on these disparities, and sharing this data with audiences like yours is a huge part of that mission."