five top things i’ve been reading (twenty-sixth edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

The Whitsun Weddings, Philip Larkin

Sense and Sensibilia, J.L. Austin

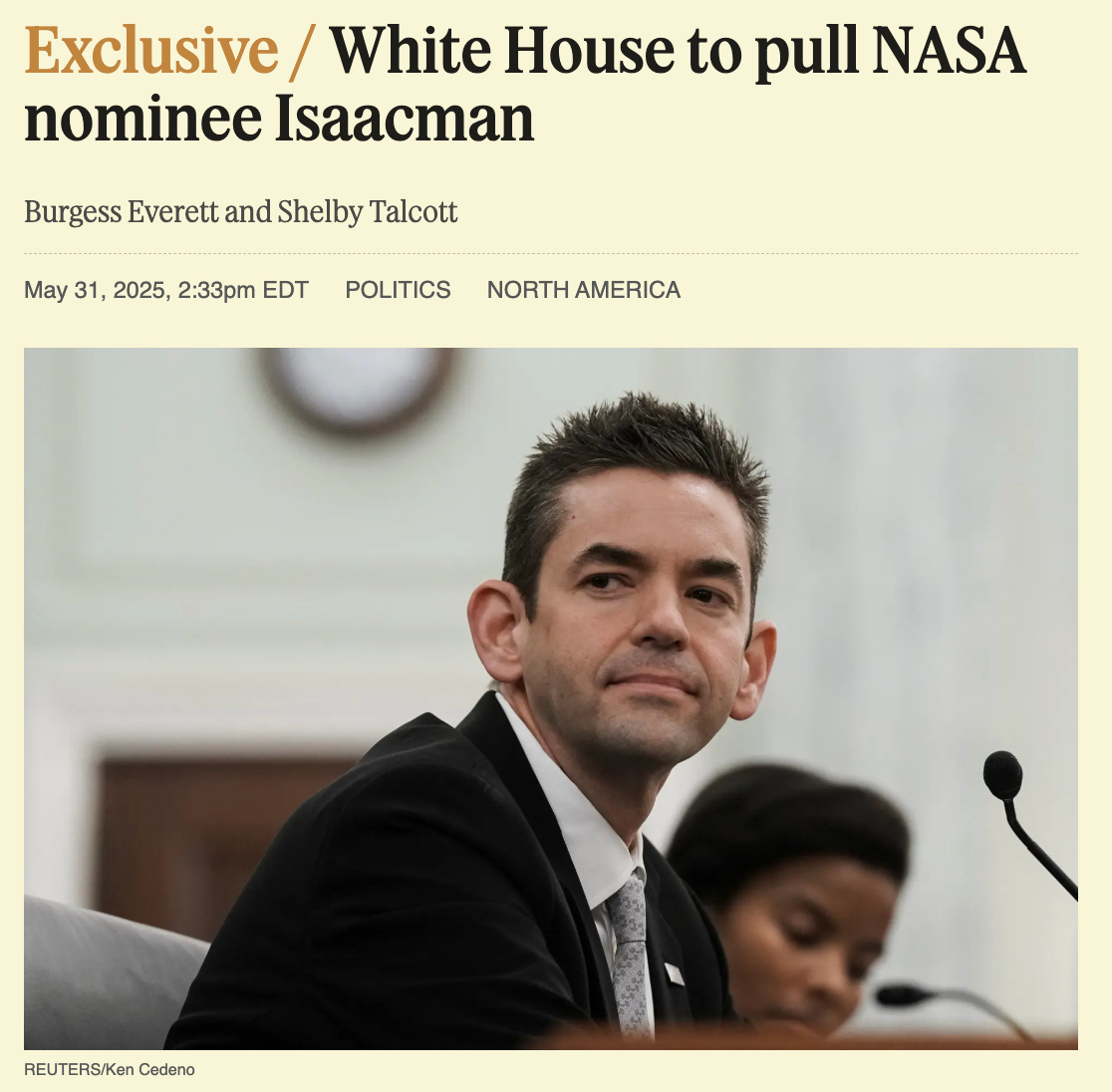

White House to pull NASA nominee Isaacman, Burgess Everett and Shelby Talcott

Cantaloupe-size hail keeps bombarding Texas, Matthew Cappucci

Andy Warhol in Iran, Brent Askari, Mosaic Theater Company

This is the twenty-sixth in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) The Whitsun Weddings is probably my favourite poetry collection, though I’ve recently decided that Larkin is no longer my favourite poet. He’s just too cynical. And that’s something I’ve been working hard to escape: the avoidance of cynicism is one of the main reasons I recently moved from England to America. Naturally I’m just as positive and enthusiastic as I find most Americans to be, yet cynicism rubs off and England is rife with it. I don’t want to be that way!

Larkin’s poetry is. Central themes of The Whitsun Weddings collection are fatalism, frustration, dismissiveness, mundanity, disappointment, and pessimism. Life is “slow dying”. Ambitions are “long fallen wide”. Self-interest rarely overlaps with the good of others. Boredom and failure are inevitable. So keep your head down, “get it learned”, and settle. The things you once valued are “a load of crap”.

Of course, there are flashes of positivity. There’s the “enormous yes” of love in Sidney Bechet. The promised awakening of the lamb in First Sight. The eagerness of the listener in Broadcast. The hands in An Arundel Tomb. But most of this is heavily couched: it’s set up to fall short; hedged with “hardly meant”. This doesn’t detract from its beauty. But it makes the collection feel brittle against the poetry I’ve enjoyed most this year: the uncontrollable positivity of Whitman, the directness of Heaney and Hughes, the everyday passion of Neruda. I love Larkin, and I’m glad I reread him this weekend. But I want to love more enthusiastically, more enormously — and most of the time, his voice cuts against that.

2) I’ve been reading J.L. Austin’s Sense and Sensibilia gradually, a chapter every so often. It’s a book about appearance and reality. And as I wrote in February, Austin pulls few punches:

“He smashes into the long-standing debate about whether we can directly perceive ‘material things’, or whether we only ever perceive 'sense-data' of them. Are you really seeing the bacon sandwich you’re about to pick up, or is it just an impression your brain created?”

Rather than fully taking a side in this debate, however, Austin spends most of Sense and Sensibilia taking apart the approach of the sense-data guys, particularly A.J. Ayer. That is, Austin is upfront from the start that he’s not going to “maintain that we ought to be realists”. He’s not going to argue that we really do perceive the sandwich directly! Rather, he wants to convince us that the sense-data guys depend on the misuse of language and “an obsession with a few half-studied ‘facts’”.

In my last update on this book, Austin had just spent Chapter Four discussing fine-grained differences between ‘looks', 'appears', and 'seems’. Chapter Five, which I read this weekend, is equally focused on the fine grain, but this time it’s the fine grain of the ‘argument from illusion’. This is an argument, used by Ayer and others, as part of their armoury to persuade us that what we perceive is sense-data. Austin has a few goes at explaining the argument from illusion, but somewhat amusingly, never does so particularly clearly. In contrast, I like this neat summary of the argument, in a Stanford Encyclopedia article by Tim Crane and Craig French:

“A. In illusory experiences, we are not directly presented with ordinary objects.

B. The same account of experience must apply to veridical experiences as applies to illusory experiences.

Therefore,

C. We are never directly presented with ordinary objects.”

In other words, and to use an Austin example, imagine you’re looking at a stick that’s been placed in a glass of water. The stick is straight, but thanks to refraction, it appears crooked. Now, the sense-data guys take from this illusion that whenever we perceive objects, our perceptions cannot be ‘direct’, because we clearly aren’t perceiving the stick directly. Chapter Five is Austin’s full-on response to the holes in this approach.

Particularly, Austin rails against the way in which ‘perceptions’ are “slipped” into the argument from illusion — ill-defined, and with the “assumption of their ubiquity”. He worries this leads to question-begging. Austin also rails against the “lumping” together of ‘delusive’ and ‘veridical’ experiences. Why, he asks, would you assume that your ‘delusive’ dream of meeting the Pope (a coincidentally topical example!) is “qualitatively indistinguishable” from meeting the Pope in real life? Ok, the Pope in your dream looks like the Pope — in the same kind of way that if you look at a white wall while wearing blue-lensed spectacles (another nice Austin example) the wall “looks blue”, and the stick in the water “looks bent” — but that doesn’t mean the experience is the same as the ‘real’ one! He goes on in this vein.

I didn’t enjoy Chapter Five as much as the previous chapters: it’s heavy-handed and meanders. Nonetheless, it’s hard to disagree with Austin’s ultimate conclusion — that the argument from illusion has some deficiencies, and they “seem [!] to be rather serious”. More on Sense and Sensibilia soon.

3) This weekend, I read quite a lot about the surprising news that Jared Isaacman’s nomination to become the next head of NASA had been withdrawn. This news was broken in a Semafor piece by Burgess Everett and Shelby Talcott. It was surprising news for various reasons, particularly: 1) as an establishment favourite who also represents the boom of the private sector (he undertook the first commercial space walk!), Isaacman was an almost universally popular pick; and 2) the appointment process was finally about to conclude after many stages and months. Everett and Talcott emphasise that NASA has been waiting for a new boss since January — a time during which the possibility of serious cuts to its budget has loomed heavy. The loss of Isaacman doesn’t just mean more uncertainty for NASA, however. It also means more uncertainty for the private space companies that depend on NASA’s business.

As ever, the best analysis of all this was by Eric Berger. Berger makes a convincing argument that the weekend’s volte-face was likely driven by concerns around “political loyalty”: Isaacman was strongly backed by Elon Musk, who’s just left the Trump administration. Most concerning, however, is Berger’s suggestion that General Kwast, who’s been tipped to replace Isaacman, is focused on “space as a battlefield”. As I’ve written before:

“while space activity has become increasingly crucial to protecting national interests, this itself reflects the growing exploitation of space for aggressive ends. According to the Space Foundation’s calculations for 2023, global military space budgets grew 18 per cent on the previous year, and comprised almost half of total government space expenditure.”

Space has long represented a new zone of warfare. Let’s hope the withdrawal of Isaacman’s nomination doesn’t end up representing a shift from exploration to combat.

4) I really enjoyed this recent Washington Post piece, by Matthew Cappucci, called Cantaloupe-size hail keeps bombarding Texas. It’s a piece about sizes and definitions. Hail is compared to softballs, grapefruits, DVDs, pineapples, baseballs, teacups, and large apples, before we reach the cantaloupe stage.

5) On Saturday night, I saw Brent Askari’s excellent two-hander play Andy Warhol in Iran, at the Mosaic Theater in DC. It’s the story of what might have happened if Warhol had been held at gunpoint in his hotel room, while in Tehran taking Polaroids in preparation for painting the Shah’s wife. The script is excellent — tight, interesting, moving, funny — as is the acting and the production. It’s on until the end of June.

lol I need you to read something on my level. Calvin and Hobbes perhaps.