five top things i’ve been reading (fifty-third edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

How Did the C.I.A. Lose a Nuclear Device?, Jeffrey Gettleman, Hari Kumar, Agnes Chang, and Pablo Robles

Night Walks, Charles Dickens

The Poems of Seamus Heaney, ed. Rosie Lavan and Bernard O’Donoghue with Matthew Hollis

The History of My Privileges, Michael Ignatieff

All My Sons, Arthur Miller, Wyndham’s Theatre

This is the fifty-third in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) I’ve written here several times about the strength of my concerns about accidental nuclear war. I’ve also written various times, here and elsewhere, about how “an instrumental benefit of knowledge-based space-tech advances, particularly in the domains of Earth observation and communications, is the widening of access to information that can prevent these potentially catastrophic confusions”.

It persistently astonishes me that there aren’t more people pushing for improvements to national and international strategies to mitigate this insane risk.

A few days ago, I read this long piece in the NYT about the various threats still posed by a nuclear generator that was abandoned sky-high in the Himalayas, back in 1965, when the weather interrupted a CIA mission. It’s a visually beautiful piece. But it only served to increase my concerns about the long-time lack of institutional attention paid to nuclear risk.

2) Yesterday, I landed at Heathrow for a few weeks back in England. So it felt apt to read the Charles Dickens essay Night Walks (1860), in which he spends a night wandering around London, trying to beat insomnia, on the lookout for other people suffering from overnight ‘houselessness’.

Dickens passes from pub to bridge to theatre to prison to market and more. The best part, however, comes when he arrives at a station. Even though I love many Auden poems, I enjoyed Dickens’ description of the postal train service more than I’ve ever enjoyed The Night Mail:

On the topic of London history, I recently enjoyed this Engelsberg Ideas piece by my cousin Keith Lowe, about the world’s first traffic signals, which “stood outside the Palace of Westminster, towering over the junction between Bridge Street and Parliament Street”.

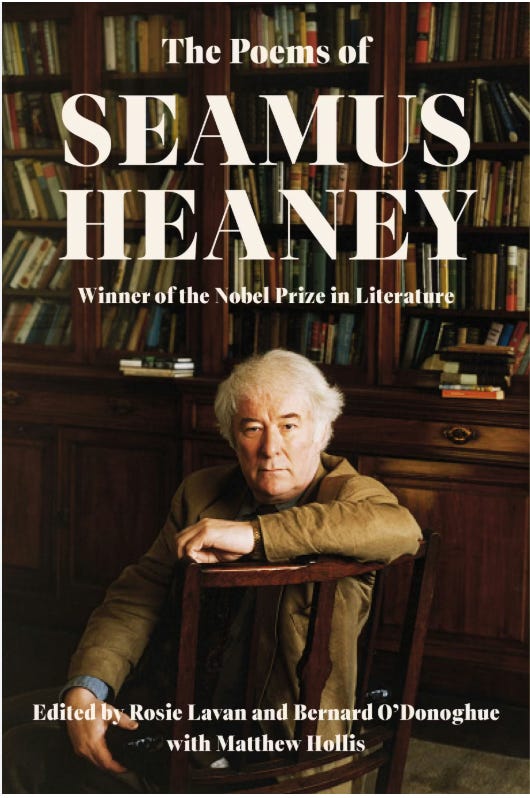

3) This week, I read the recently published collected poems of Seamus Heaney. I focused almost entirely on the poems, rather than the notes provided by the editors. And, as ever with Heaney, I struggled to find anything — in these hundreds of poems — to dislike. Rather, most of all these poems, all these lines, even all these words, I love.

I particularly love the hardcore realism of the collections North (1975), Field Work (1979), and Death of a Naturalist (1966). As I said on The Pursuit of Liberalism podcast, a few days ago:

“I think for me, though [what makes me think Heaney is a liberal is] the realism. He wants to get at the truth, I think. And he wants to get at the truth about what it is to be human — what it is to be human living in a natural world. This seems to me deeply liberal, also. I mean, if you think, you talked about how he in the beginning was writing in the 60s and 70s. This is a time of postmodernism. He is the most anti-postmodernist poet you could imagine.”

But there are 70 minutes of Henry Oliver and me rhapsodising and arguing about Heaney in that episode, so I’ll leave the topic here for now!

4) On the topic of podcasts, I just published the latest episode of my philosophy podcast, Working Definition. This latest episode is on the topic of liberalism, and it stars my excellent friend Michael Ignatieff. During the episode, we talk about various of the many things Michael has written, including his (recently revised) biography of Isaiah Berlin (1998), and this recent Substack piece about the relation between liberalism and revolution.

A piece we didn’t discuss, however, is this 2024 Liberties essay, on the topic of privilege. I often think about this section, in which Michael argues that the lifetime “immunity” gained from having been the recipient of parental love is perhaps the greatest privilege of all:

“At the very center of this memory is this certainty: I am holding my mother’s hand. I can feel its warmth this very minute. Nothing can harm me. I am secure. I am immune. I have clung to this privilege ever since. It makes me a spectator to the sorrows that happen to others. Of all my privileges, in a century where history has inflicted so much fear, terror, and loss on so many fellow human beings, this sense of immunity, conferred by the love of my parents, her hand in mine, is the privilege which, in order to understand what happens to others, I had to work hardest to overcome.”

While we’re on philosophy, yesterday I enjoyed reading Ned Block’s recent article Can only meat machines be conscious? I find its title a little more striking than its arguments, but maybe I’ll write about it here sometime.

5) Last night, I went to see Arthur Miller’s All My Sons (1946) at Wyndham’s Theatre. This extract from the programme (the play bill!) tells us about the views of Ivo van Hove, who directed the production:

“To Van Hove, it is a ‘misunderstanding’ that Miller’s work is so often staged ‘very realistically and very naturalistically’, when the slow self-destruction of his characters holds the potential for a reading more akin to the emotional savagery of Greek tragedy.”

Now, perhaps unsurprisingly, one of the things I love most about Miller is his realism. And, as it happens, I don’t think that realism and naturalism are mutually exclusive from emotional savagery or from Greek tragedy as a genre. Moreover, when the curtain rose, my first view of the Wyndham’s set — bare aside from a massive full-moon-shaped window hanging above a stylised fallen tree — made me think more of Debussy’s Pelléas than the post-war Midwest.

Nonetheless, this is one of the best productions, of anything, I’ve seen in a long time. Maybe ever. It’s on until early March, so if you’re in London before then, you should go!