five top things i’ve been reading (thirty-seventh edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

The beastly dilemma facing Europe’s zoos — to cull or not to cull, Oliver Moody

A Clean Sweep: An interview with John Broome, Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics

Millennium People, J.G. Ballard

The Ultimate Crime, Isaac Asimov

Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants, Stevie Wonder

This is the thirty-seventh in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) “Would you like to donate an animal for food?” Over the past week, there’s been much criticism circulating about the offer made by Danish zookeepers to take unwanted pets off the hands of the public and into the mouths of the zoo’s inhabitants. A recent Times article by Oliver Moody suggests this is only the tip of the iceberg, however, when it comes to the morally problematic behaviour of zookeepers.

The context of Moody’s article is set early on, by the following comment:

“We have this situation with the apes, with the big cats, with the bears. Everywhere we are having to ask ourselves: what do we actually do with the animals?” said Dag Encke, the director of Nuremberg Zoo. “It varies from species to species but on the whole we have got so good at producing and breeding them that by now we have filled up the zoos.”

After telling us about the healthy lion and tiger cubs recently “put down” in German zoos, Moody goes on to catalogue the different approaches to population control — or “management euthanasia” — found within the zoos of different nations.

There’s what Moody calls the “unsentimental” approach, exemplified by the Danes who, it turns out, look beyond the household when sourcing animal feed. In 2014, we learn, a zoo in Copenhagen shot an extraneous baby giraffe named Marius, and fed his “publicly dissected” body to the lions. Then there’s the “pragmatic” approach, exemplified by the Germans who, according to Moody, act on the principle that a zoo animal can be used as food for another zoo animal, as long as it’s an animal that “a human could reasonably eat”. I could write a whole piece about that principle alone, but I’ll restrict myself to quoting in full the most astonishing bit of consequent human reasoning:

“There are certain popular animals where you have to stop and think twice,” said Encke. “For example, with the giant kangaroos we had to consider whether they were recognised [as food]. In the end we decided they were recognised, because you can buy kangaroo meat in tins. So we fed the kangaroos [to the carnivores] in Nuremberg.”

Moody’s list of national culling approaches continues. Sure, there are countries like the USA where, he tells us, “strong cultural taboos” militate against the “killing of healthy zoo animals”. But he also emphasises that zoos in most countries are not legally required to report on such matters. And he strongly implies that UK zoos, in particular, carry out such practices without talking about it.

We can stop here, however, because all of these details are way downstream of the real problem. The real problem, of course, is that keeping animals in cages — whether for entertainment purposes, or conservation purposes, or education purposes, or whatever — comes with many serious consequences. Zoos are the result of human choice. Zoos make wild animals our dependents. You can hardly confine a load of animals to cages, and then treat as some kind of frustrating inconvenience — an inconvenience to be “managed” — the fact that these animals have become too numerous to fit!

Yet there’s this passive inevitabilitarianism that pervades the article and the comments of everyone Moody quotes. That zoo overpopulation is a problem to be mitigated is treated as a fundamental premise. This is bizarre. It’s also wrong — not just morally, but also, surely, factually. Yeah, shoot them! Feed them to each other! What else can we do!? The size of zoos is fixed forever, and the fact that we keep animals in such places can never be changed!

There are hard questions to be answered about human obligations to wild animals in the wild. And there are hard questions to be answered about human obligations to the types of animals we’ve made dependent upon us, whether through caging or domestication. These include questions about how to meet the dietary requirements of carnivores. But we can’t just jump ahead to those questions, here! If the reason you’re feeding the baby giraffe to the lions is that you’ve got too many baby giraffes for the size of your cage, then something has gone very wrong.

2) I both enjoyed and was frustrated by this interview with the Oxford moral philosopher John Broome, recently published in the Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics. I disagreed with the substance of most of Broome’s answers, straight off and on hard reflection — particularly on the topics of what a reason is, what teleology is, and the relation between equality and fairness. But thinking about all these things brought me enjoyment rather than frustration.

It was the incompleteness of the piece that frustrated me. It often felt as if Broome was skating over the broader and deeper reasons (!) he holds his positions. This, of course, is a natural risk for a relatively short summary interview, aimed at pinning someone down on so many complex topics. Many of the questions posed to Broome are highly specific, so it’s all a bit pneumatic scattergun.

Near the end, Broome is asked about doing philosophy, doing economics, and the benefits of combining the two. “I recommend philosophy for the excitement of pure thought” is his penultimate comment, and I’ve rarely agreed with anyone more without really knowing what they meant.

3) My favourite J.G. Ballard novel is Running Wild. I automatically thought of it the other day when I saw people posting on Twitter about a new movie in which a load of kids from one particular community disappear overnight. Perhaps that’s why I decided to read his Millennium People (2008) this weekend.

Millennium People is the story of David Markham, a middle-class guy who gets caught up in a violent middle-class struggle against middle-class culture. Like most of the characters in this novel, Markham is either impossibly naive or a bit of a psycho. It’s a good fast read: it has impetus, tight writing, meta humour, and an implicit underlying theory of the effects of modernity on interpersonal relations.

Of course, if you’ve read any Ballard novels before, you probably already know most of this. I hadn’t read any in a while, and one thing I can’t remember thinking so much previously, was how Houellebecq it all is.

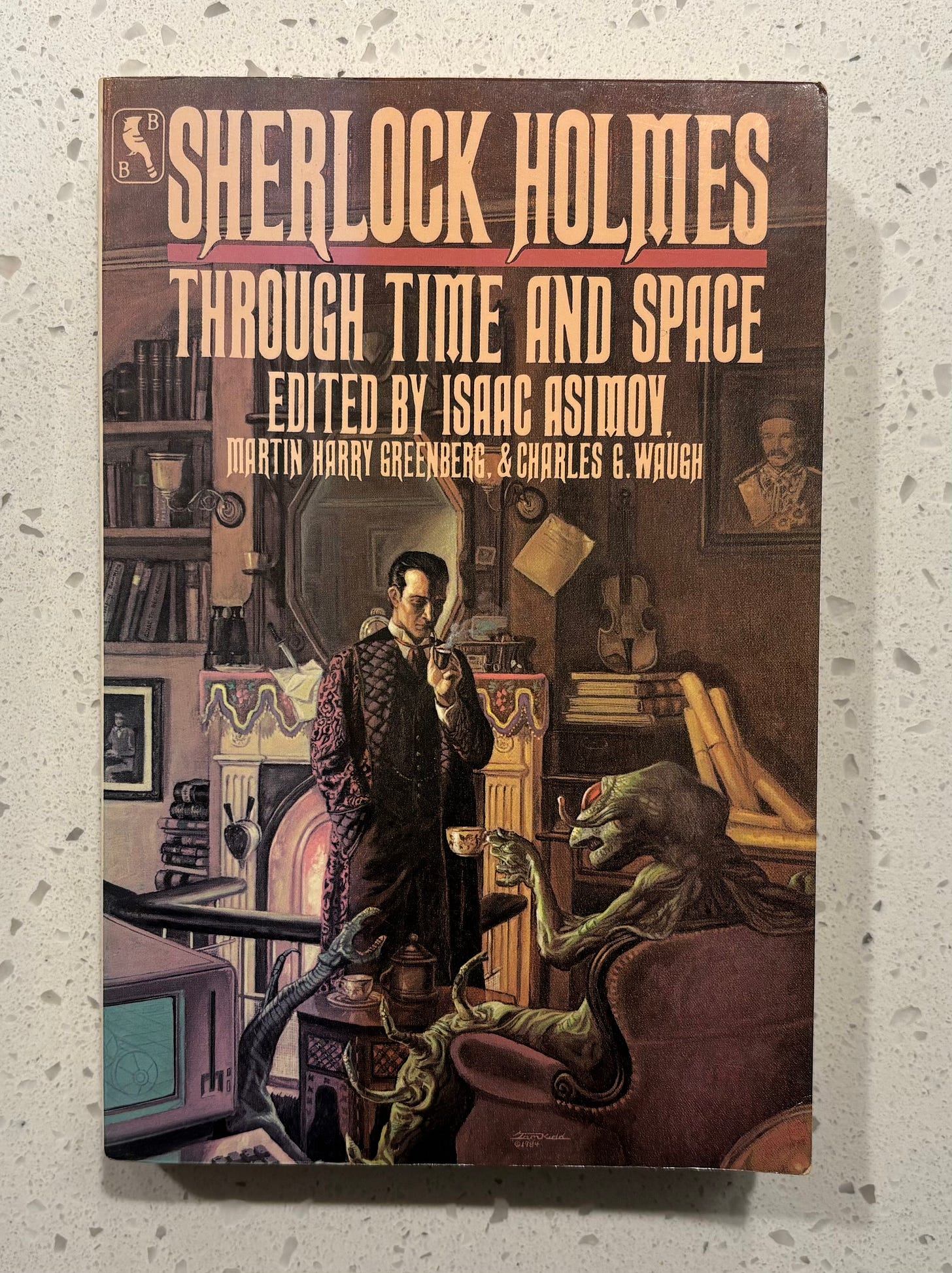

4) I was obsessed by Sherlock Holmes when I was a kid. So I’m sad that I didn’t know, back then, about the Isaac Asimov edited collection, Sherlock Holmes Through Time and Space. This collection brings together stories by writers including Doyle and Asimov, “in which you will meet the spirit of Sherlock Holmes in the form of animals, robots, extraterrestrials, and so on”.

At the moment, I feel like rationing myself to one of these stories every few weeks, so I’ve only read Asimov’s so far. It’s a comment on the value of deductive reasoning, and it’s pretty good. You get a central character based on Asimov, trying to come up with a satisfying ‘Sherlockian’ argument to prove his worth to his fellow members of a society of Holmes enthusiasts. You get the conjunction of astronomy and evil. You get no Holmes, but you kind of get a Watson.

5) I listened to a lot of Stevie Wonder when I was in Ghana last week. Partly because I learned before going that he’s a Ghanaian citizen. And partly because I learned before going that his music is really great. I also think he’s right that we should think much harder about our moral obligations to plants.

"Millennium People, J.G. Ballard"

One of my all time favourite books. Just saying.

I'd buy the Asimov book for the cover alone!