five top things i’ve been reading (forty-first edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

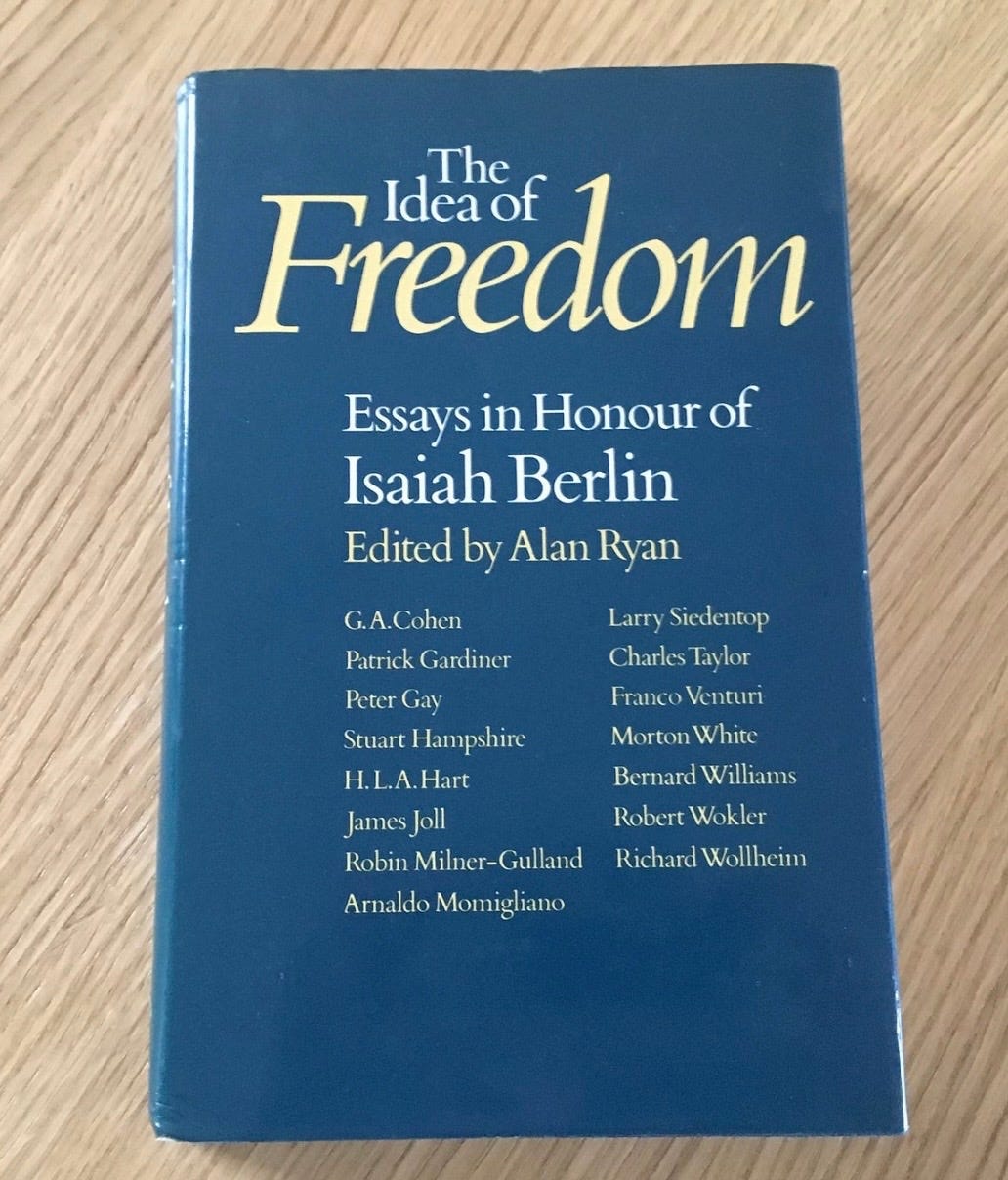

Conflicts of Values, Bernard Williams

If America Should Go Communist, Leon Trotsky

NASA Says Mars Rover Discovered Potential Biosignature Last Year, Jessica Taveau

The Inexplicable Appeal of Spicy Food, Daniel Pallies

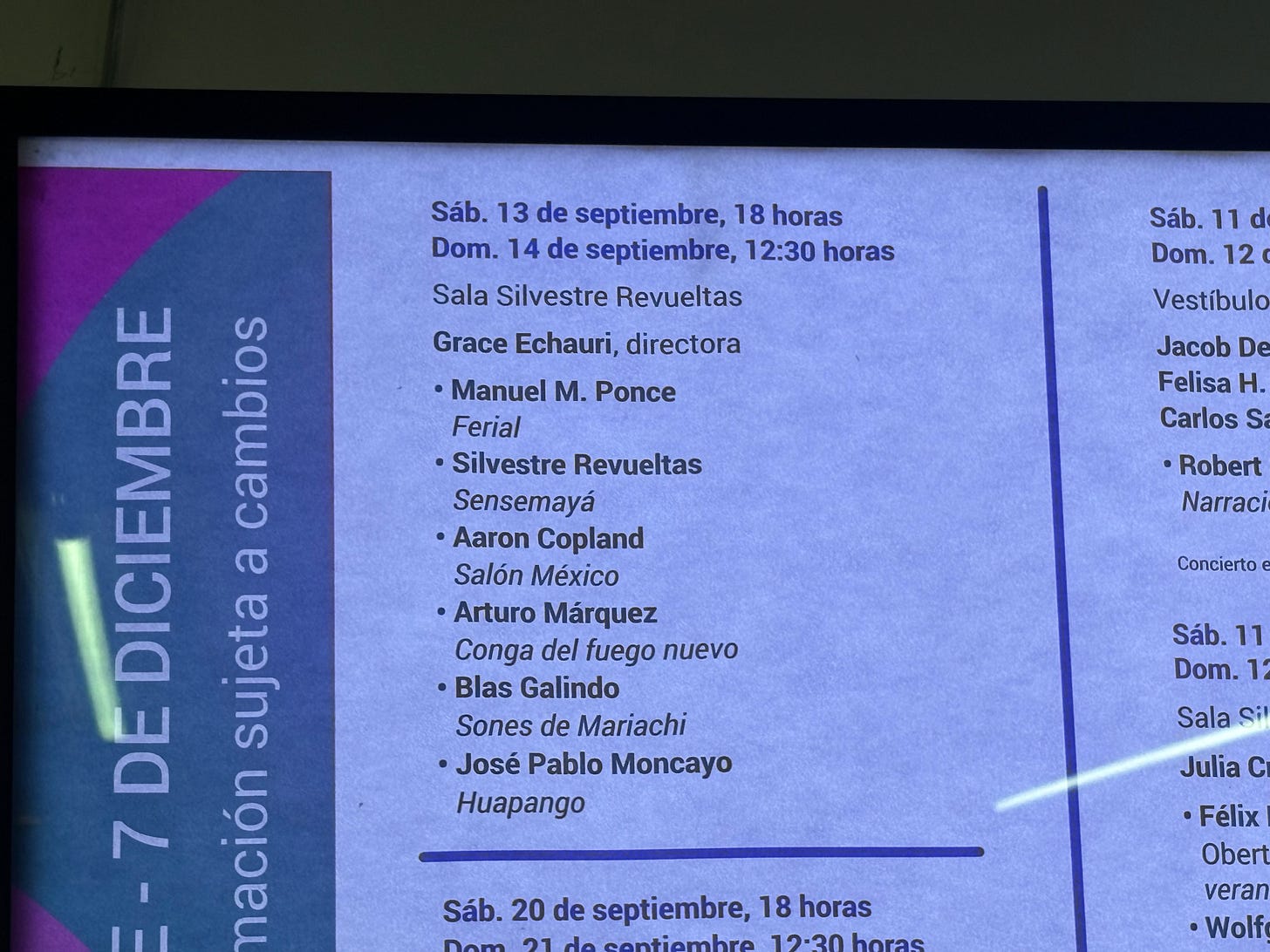

Concierto Mexicano, Mexico City Philharmonic, conducted by Grace Echauri

This is the forty-first in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) Bernard Williams’ Conflicts of Values (1979) is a paper about conflicts. Not just conflicts between values, but conflicts between other things, too — particularly obligations, virtues, and the public and private domains.

The final of these conflicts is saved for the concluding paragraphs of the paper. Whereas Williams makes extended appeals to conflicts between obligations, and to conflicts between virtues, as routes into discussing the possibility and experience of value-conflict. In particular, he focuses on one-person value-conflict. That is, the inner tussling an individual might face in relation to seeming tensions arising in relation to the furthering of multiple values, as opposed to the kind of value-conflict that might occur between two or more people disagreeing about such matters.

Williams’ discussion takes place in the context of Isaiah Berlin’s influential view that values are plural, irreducible to each other, and can conflict. Williams begins by telling us that he agrees with Berlin that value-conflict is “necessarily involved in human values, and to be taken as central by any understanding of them”, but that he goes further than Berlin might, by holding that the “need to […] overcome” conflict can be a matter of historical contingency as well as a matter of logic or reason. These opening statements signal Williams’ paper’s dual focus on metaphysical truths about value-conflict and on human ways of dealing with seeming instances of it.

I find that both of these focuses are dulled, however, by Williams’ explicit sidestepping of the relevance of moral objectivity: “I shall not try to pursue such questions here”! Minimally, this makes discussion of concepts like ‘moral impossibility’ necessarily (!) fuzzier. But this sidestepping also makes it extra frustrating that Williams implicitly appeals to the value of moral objectivity to support his commitment to the existence of ‘tragic’ obligation-conflict. I mean, read this:

“the experience of ultimate moral conflict is precisely one which brings most irremovably with it the impression of objectivity; that there is nothing that one decently, honourably, adequately, can do in a certain situation seems a kind of truth as firmly independent of the will or inclination as any truth of morality seems.”

A further unanswered question lurking beneath this paper is the question of whether ‘ought implies can’. At one point, Williams poses a critical question for “those who rely heavily” on this Kantian maxim, but Williams himself doesn’t get close to explaining what ‘ought’ might mean if it were free from ‘can’. And again, when he asks “[w]hat would have to be true of the world and of an agent that it should be impossible for him to be in a situation where whatever he did was wrong?”, I find myself wanting to know what exactly he thinks this question means outside of a commitment to objective moral truth. A passing dependence on intuitionism in the final section of the paper doesn’t help with any of this, either.

Now, it might sound from what I've written that I didn't enjoy or value reading this paper. But that's not true! One of my favourite things is thinking hard about the most serious philosophy I can find that I strongly disagree with — whether my disagreement is with its conclusions, methods, both, or whatever. Even better, of course, is when reading such things helps me to realise that I've been in the wrong. I'll be thinking about this paper for a while yet.

2) I was in Mexico City for the weekend, and went to the Trotsky Museum in Coyoacan. This museum takes the form of one excellent main display room, appended to the large fortified house (and its enclosed garden) where Leon Trotsky lived for his final year and was sadly assassinated.

After visiting the museum, I read If America Should Go Communist (1934). This is an article Trotsky wrote for the U.S. magazine Liberty, during the period when, according to the foreword appended to the article's 1951 reprint by the Fourth International, "following the Great Depression, there was considerable popular interest in the prospects of a Communist America".

Trotsky’s main Marx-like aim, in this article, is to convince us that economically-developed democratic America would institute a preferable form of communism to destitute Tsarist Russia. ‘Soviet America’ would be less bureaucratic! And its necessary bureaucratism — just a bit of mild “one-year, five-year, ten-year plans of business development” — would benefit from “vigorous electoral struggle and passionate debate in the newspapers and at public meetings”!

That said, of course, “private capital [would] no longer be allowed to decide what publications should be established”. And Trotsky’s attempt at posing an alternative method for determining the content and distribution of the ‘free’ press — based on proportional representation! — signals the long-run feasibility and legitimacy problems of attempting to do away with markets.

I’ve written here before about why I think private property is both necessary and valuable to political society. And my arguments in that piece — particularly my argument that you can’t discount the productive and distributive benefits of private-property systems to abundant places — cut away at Trotsky’s dream of successful American communism. Nonetheless, his article is interesting throughout. I particularly enjoyed its tactical Americanisms: I bet you’d never imagined Trotsky using the phrase "dead wrong”!

3) Over the past week, I’ve enjoyed reading various pieces about the astonishing discovery of what NASA calls “the identification of a potential biosignature on Mars”. I’ve long assumed there’s life of some kind in other places aside from Earth, and Mars keeps becoming a stronger and stronger contender. It really surprises me that more people aren’t more excited about this latest news.

4) This recent short piece by Daniel Pallies raises the important question of why many people opt to eat food that’s so spicy it brings about a “burning feeling”. Pallies considers four answers: 1) that the burning feeling isn’t unpleasant; 2) that the burning feeling is unpleasant but adds to the overall pleasantness of the meal, “like the bitter medicine you take in order to get healthy”; 3) that if you desire the burning feeling, then this makes experiencing the burning feeling a good thing for you; and 4) that tolerating the burning feeling counts as, and is experienced as, an accomplishment.

Some of these answers, therefore, focus more on whether eating pain-inducing spicy food is good for us, rather than why we do it. And I think that the ongoing puzzlement in which Pallies ends his piece might be alleviated somewhat if he considered the most obvious answer to the ‘why’ question: because the spices that bring about these burning feelings also taste great!

Nonetheless, it seems highly likely that many people who opt to eat spicy food would feel shortchanged if its great taste persisted but suddenly all, or most, of its ‘heat’ disappeared. And while addressing this problem goes beyond Pallies’ original ‘why’ question, I think a combination of his first and fourth answers is useful here.

That is, my guess is that most spicy-food-eaters, like me, set some limit to the spiciness of the food they eat — a limit which tracks the point at which eating becomes seriously painful as opposed to HOT! And my further guess is that the remainder of spicy-food-eaters — those who go beyond that limit out of choice — are either thrill-seekers or show-offs, who find some sense of accomplishment in enduring the pain. I ate a load of spicy food in Mexico and it was delicious.

5) On Saturday, I went to an excellent concert of Mexican classical music (and Copland's wonderful El Salon Mexico) played by the Mexico City Philharmonic. My favourite was Silvestre Revueltas’s Sensemayá (1938). Such great minimalism.