five top things i’ve been reading (forty-eighth edition)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

My Story, Helen Keller

Experience and Poverty, Walter Benjamin

To the shoemakers and the ship-builders: on publicly-engaged philosophy and AI ethics, John Tasioulas

How AI Is Changing Higher Education, Chronicle Review

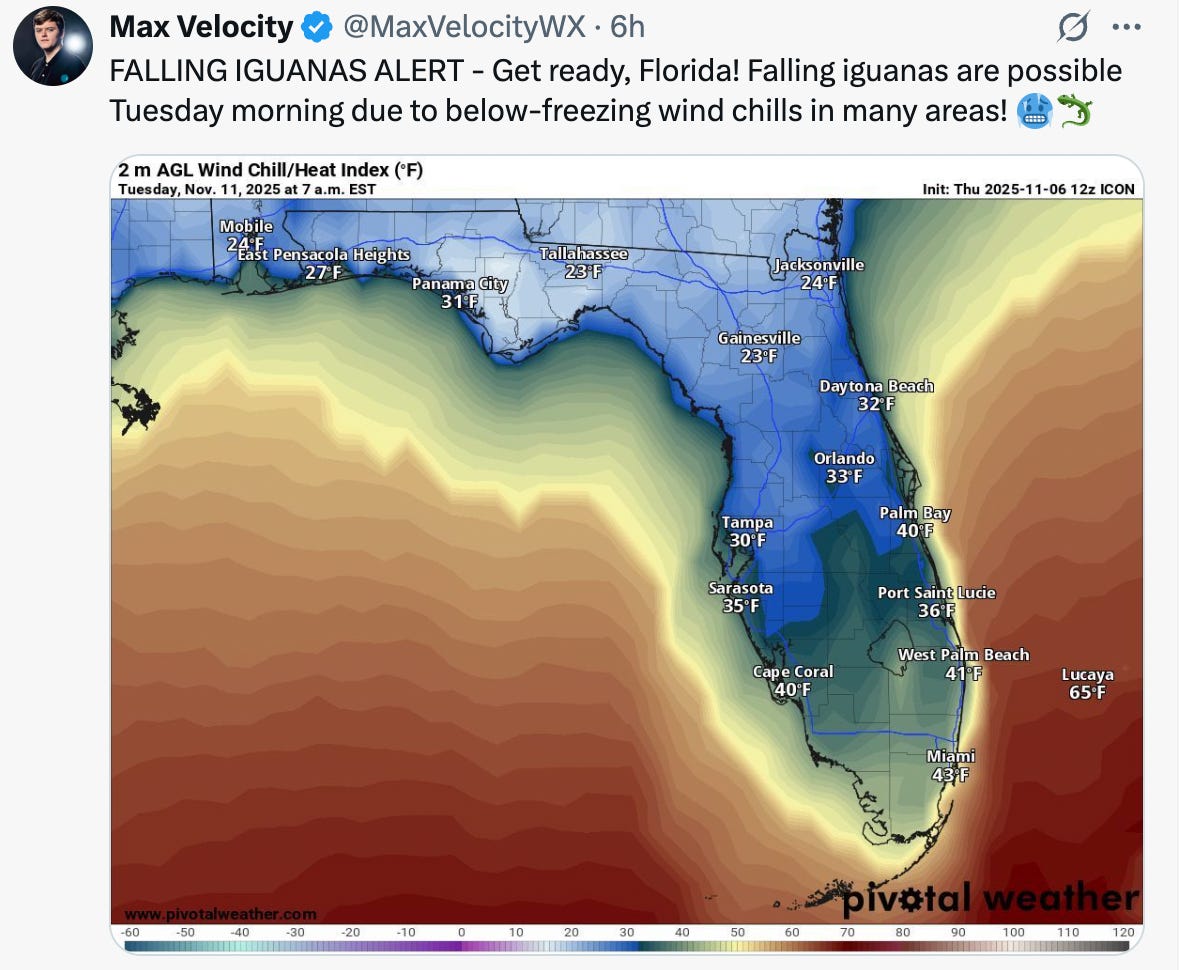

Falling iguanas alert tweet, Max Velocity

This is the forty-eighth in a weekly series, a little later in the week than usual.

1) This evening, I read Helen Keller’s autobiographical essay My Story (1903), and have many questions as a result. Keller was born fully capable of seeing and hearing, but became deaf and blind at the age of 19 months. She wrote this essay when she was twelve.

My copy of the essay forms part of an NYRB Keller collection (2003), which includes an introduction by the literary critic Roger Shattuck. I found Shattuck’s introduction pretty much unbearably written. It’s full of phrases that are either or both cloying or morally annoying, such as “her very being”, and “fully human hybrid of freak and angel”. My least favourite sentence was: “A twenty-one-year-old half-blind teacher, sent from Boston to rural Alabama, was able to wake the child princess and tame the vixen”.

Nonetheless, I learned some interesting things from this introduction about Keller’s life and her writing — including details about claims of plagiarism she faced in relation to a short piece of fiction she wrote the year before this essay. I intend to read more about Keller. But for now, I’ll take what she says at face value, and continue to think hard about the philosophical questions arising from My Story.

In particular, the following section, which describes experiences from when Keller was six, made me want to return immediately to Quine:

“That afternoon, besides “doll”, I learned to spell “pin” and “hat”, but I did not understand that everything had a name. […]

Teacher had been with me nearly two weeks, and I had learned eighteen or twenty words, before that thought flashed into my mind, as the sun breaks upon a sleeping world; and in that moment of illumination the secret of language was revealed to me, and I caught a glimpse of the beautiful country I was about to explore.

Teacher had been trying all the morning to make me understand that the mug and the milk in the mug had different names; but I was very dull, and kept spelling “milk” for mug, and “mug” for milk until teacher must have lost all hope of making me see my mistake. At last she got up, gave me the mug, and led me out of the door to the pump-house. Some one was pumping water, and as the cool, fresh stream burst forth, teacher made me put my mug under the spout and spelled w-a-t-e-r. Water!”

I have many questions.

2) I also read Walter Benjamin’s Experience and Poverty (1933), this evening. I think I hadn’t read any Benjamin, and certainly not this essay, since I studied aesthetics as an undergrad, twenty years ago. I’d forgotten how conservative it is.

As back then, I find this kind of writing — as attractive as it can be — very frustrating, for its lack of clarity of argument. That said, I think I like it more now than I did in those days, which surprises me. Beyond that, there are ideas in this essay, which I realise now, had stayed with me.

There’s Benjamin’s opening observation, and perhaps thesis, that the first world war was so horrific that a generation had done away with experience as a source of value and a guide. Here, I find the presumably purposeful conflation between “poverty of experience” qua having had few or even no experiences, and “poverty of experience” qua having had bad experiences, difficult to accept. I remember it’s best not to presume about these kinds of texts, however.

There are also these interesting effective railings against the (other) modernists, which really are railings against the conditions of the time. There’s a great line about Scheerbart being “interested in the question of what completely new, lovely, and lovable creatures our telescopes, our airplanes, and rockets”… which I’ll close off before the sentence shifts. And of course there’s the next war.

I can see now, in a way I struggled to see previously, that a reasonable — perhaps even demanded — approach to reading such texts is to let it ‘flow over you’ (I hate that phrase). I’d still rather think about it, for all I’m left dissatisfied by ambiguities.

3) I was glad to read this new essay about the value of the humanities in the age of AI, by my excellent friend and ex-boyfriend John Tasioulas. John and I have enjoyably different views on most matters of politics and economics, and on many matters of philosophy. But one thing we strongly agree about is the badness and wrongness of consequentialist moral theories.

John’s criticism of the status quo bias displayed towards consequentialist reasoning by “the powerful scientific, economic and governmental actors in this field” should be read by anyone who thinks that complex questions of morality — to do with AI, or indeed anything — can be reduced down to the “optimal fulfilment of human preferences”. You can find this in the section of the essay entitled ‘the dominant approach’.

4) I’ve already written here about the short piece I contributed to the Chronicle of Higher Education’s Chronicle Review forum on ‘How AI Is Changing Higher Education’.

However, my piece — in which I argue that AI has the potential to “move beyond human epistemic limitations in educational institutional design in ways we can’t yet imagine” — is one of 14 pieces published together as a set, addressing the question at hand. I haven’t read them all yet, but those I have, I enjoyed.

5) Earlier this year, I wrote here a couple of times about my new interest in Extreme American Weather. I wrote about learning that “hail is compared to softballs, grapefruits, DVDs, pineapples, baseballs, teacups, and large apples, before we reach the cantaloupe stage.” And I wrote about learning about “earth-eating supercells, red polygons, epic shelf clouds, and multivortex gustnadoes”.

So it’s hardly surprising that, when I read this tweet this evening by a Twitter Meteorologist, I assumed that a “falling iguana” was a specialist term for another kind of extreme American weather.

Thirty odd years ago I made a visit to my parents in Bridgeport, CT and during the trip wound up a the house of one of my cousins. Her husband Bruce found an stray iguana in Bridgeport, brought it home to the suburbs, and built it a habitat. He took me in to see it, and said, "This is Moana the Iguana." I said, "I knew a girl named Moana Diamond when I was young." Bruce looked a bit shocked, because he had worked with Moana Diamond at the Bridgeport Cabaret and named the iguana after her.

So I go back to my parent's house and say to my elderly mother, "Bruce know Moana Diamond!" and my mother replies, "What do you mean, Bruce doesn't want a diamond?"

Life is a sitcom.