five top things i’ve been reading (twentieth edition!)

the latest in a regular 'top 5' series

The Right to Lie: Kant on Dealing with Evil, Christine Korsgaard

City of Glass, Paul Auster

The Moon Should Be a Computer, Omar Shams

The Best Books on Wine, Jancis Robinson interviewed by Rupert Wright and Sophie Roell

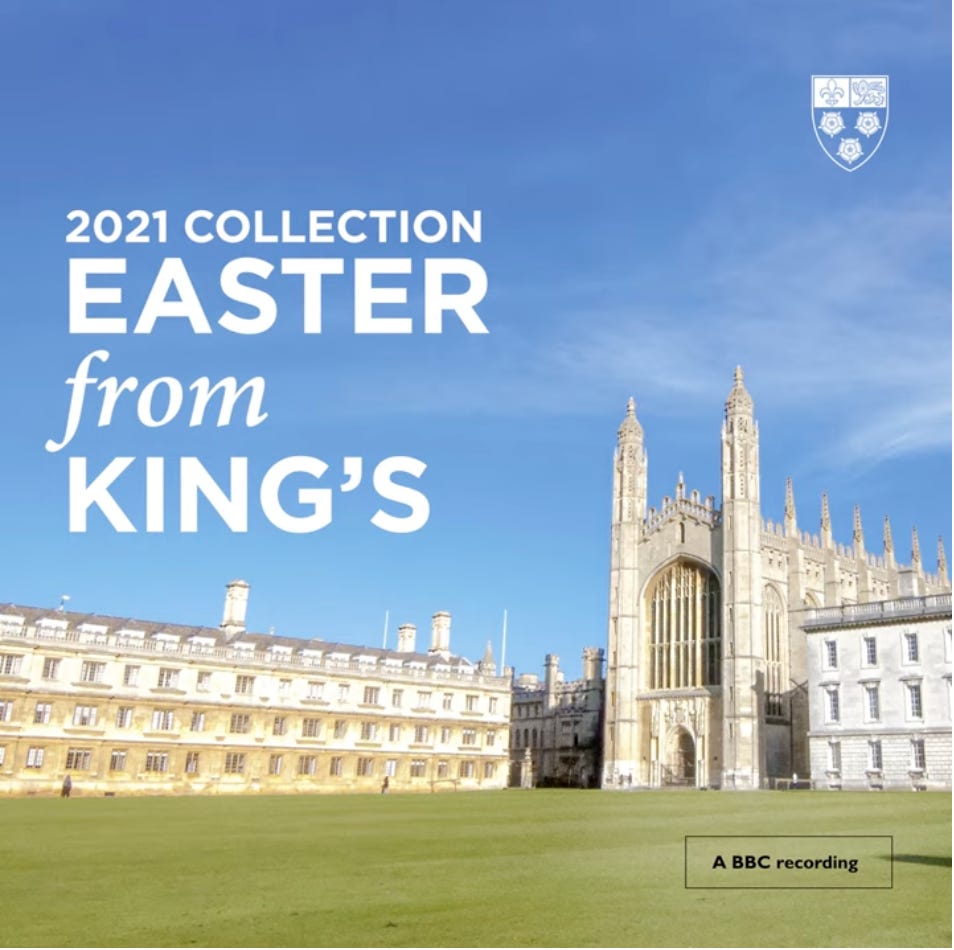

Were You There When They Crucified My Lord? arr. Richard Lloyd

This is the twentieth (!) in a weekly series. As with previous editions, I’ll move beyond things I’ve been reading, toward the end.

1) The Right to Lie: Kant on Dealing with Evil is a 1986 paper by Christine Korsgaard, one of the leading Kantians of our time. The core question Korsgaard addresses is: ‘Does Kant really tell us it’s always wrong to lie?’. Or, as she puts it, “One of the great difficulties with Kant's moral philosophy is that it seems to imply that our moral obligations leave us powerless in the face of evil.” Korsgaard addresses further questions in this paper, including, ‘Does Kant really tell us we’re to blame for everything that follows every lie we tell?’, and ‘You haven’t forgotten the other parts of Kant’s moral theory beyond the Formula of Universal Law, have you!?’. But her main focus is this question about the permissibility of lying.

Korsgaard addresses the lying question in the context of a famous story told by Kant. No doubt you know it. There’s a knock at the front door, and hey, it’s a murderer, asking whether his intended victim is at home! Over the course of the paper, Korsgaard tries to persuade us that Kant’s take on this story isn’t as simplistic as the stereotyped assumption in which he shouts, “Of course you must tell the truth to the murderer and let his intended victim die!”.

First, Korsgaard quotes a section of Kant connecting epistemic fallibility, causation, and blameworthiness. Perhaps, Kant says, it was no longer true that the intended victim was at home. Because perhaps, Kant says, the intended victim had snuck out of the house without you realising. In such a case, Kant says, if the murderer found his intended victim in the street, then it was your lie that sent him there, and “you might justly be accused as the cause of [the victim’s] death”! Okay…

Second, Korsgaard makes a complicated attempt to “evade universalisation”, by concluding that perhaps we can interpret Kant as permitting us to lie to liars. It’s an interesting argument, if ultimately sleight of hand. But by this stage it seems clear that the title of this paper is overly seductive: there is no ‘right to lie’ being established here!

Nonetheless, Korsgaard saves her strongest argument for last: that all moral theories, including Kant’s, should include special space for us to attend to evil. Indeed, the most interesting moment of the paper comes at the very end, when Korsgaard briefly analogises this ‘special space for evil’ idea with Kant’s approach to the laws of war. She describes how, on the latter, “peace functions not as an uncompromising ideal to be lived up to in the present, but as a long-range goal which guides our conduct even when war is necessary”. Korsgaard employs this analogy, therefore, to conclude that perhaps even Kant himself might have accepted a “special principle” type “modification” of his absolutist approach to lying.

Most of Korsgaard’s paper, however, isn’t aimed at telling us what Kant might’ve thought. Rather, it’s an attempt to save Kantian moral theory from standard accusations of “rigorism”. If like me, you’re not a Kantian already, then this paper probably won’t convert you. But it might get you past the front door.

2) Paul Auster’s Baumgartner (2023) is one of the best novels I’ve read in the past couple of years. His Brooklyn Follies (2005) is one of the best I’ve read in the past decade. This week, I returned to the three novellas that make up Auster’s most famous book, The New York Trilogy (1987). Last time round, I loved the first of these novellas, City of Glass, but didn’t get past the second. I’ll return to the second and third, here, next week.

City of Glass centres on some strange happenings in the life of Daniel Quinn, a New York-based writer who’s mistaken for a private detective named Paul Auster. This self-referential quality, alongside its urban setting, might make some people say that City of Glass is a modernist novella. The gradual reveal of its narrative layers might make others say it’s postmodernist. But all this just reminds me how frustrating I find the lack of neat conditions for these literary genres!

I also can’t say much about the plot of this novella without wrecking it for you, if you haven’t already read it. But I’ll tell you there was a moment, about halfway through, when the sense of dread that had begun to build almost made me stop reading. I’m glad I didn’t. Auster’s a great writer: his sentences are neat and never cloy; he grounds experimental twists in everyday settings, full of fantastically dense descriptions of places and things; his characters seem real, even when they aren’t based on himself. It’s hard to think of many better.

3) I enjoyed this recent Palladium piece, in which Google AI engineer Omar Shams argues that the moon is the obvious place to build and run the ‘compute’ needed to ensure that AI progress continues to compound. The moon, Shams emphasises, has plenty of space for the necessary infrastructure, wouldn’t become over-heated if used in this way, is littered with useful silicon, and is free of “regulatory hurdles”.

Contrary to Shams’ implication, I’m unconvinced that thermodynamics is the only reason that astonishing AI progress will tail off at some point. I’m also unconvinced it’s a good idea for anyone or any nation to land-grab the moon! This isn’t because I think international law — which currently prohibits appropriating, and for the most part building on, spaceland — is the dream solution loved by its strongest advocates (hey again, Kantians!). Rather, as I’ve argued elsewhere, there’s a market-based liberal solution to solving the space property problem that’d be much better, all round, than either the status quo or ‘first come first served’. Shams’ piece is a fun read, anyway, and impressively ambitious.

4) As I’ve mentioned before, my favourite wine book is Cork Dork, by Bianca Bosker. In this new Five Books interview, the leading wine critic Jancis Robinson makes a strong case for five other wine books. I enjoyed reading it. But I struggled with Robinson’s commitment to presenting herself as a hardcore aesthetic anti-objectivist. “Everything with wine is subjective,” she says up front, and reinforces many times. As it happens, I’m almost in agreement with her sentiment. But I wouldn’t go as far as ‘everything’, and it’s hard to see how doing so coheres with being a wine critic! After all, I enjoyed this interview in large part because I’m convinced that Robinson knows facts — about wine’s qualities, as well as the industry that makes and sells it.

5) On Friday, I listened several times to this Richard Lloyd arrangement of the spiritual Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?. The treble counter-melody at the start of the ‘rolled the stone away’ verse is particularly effective. But it’s all wonderful. Lloyd was a one-time organist of Durham Cathedral, and back when I was living in Durham, the cathedral choir always sang this piece on Good Friday. I don’t go to church any more, but I hope they still sing it there.